January 19, 2024

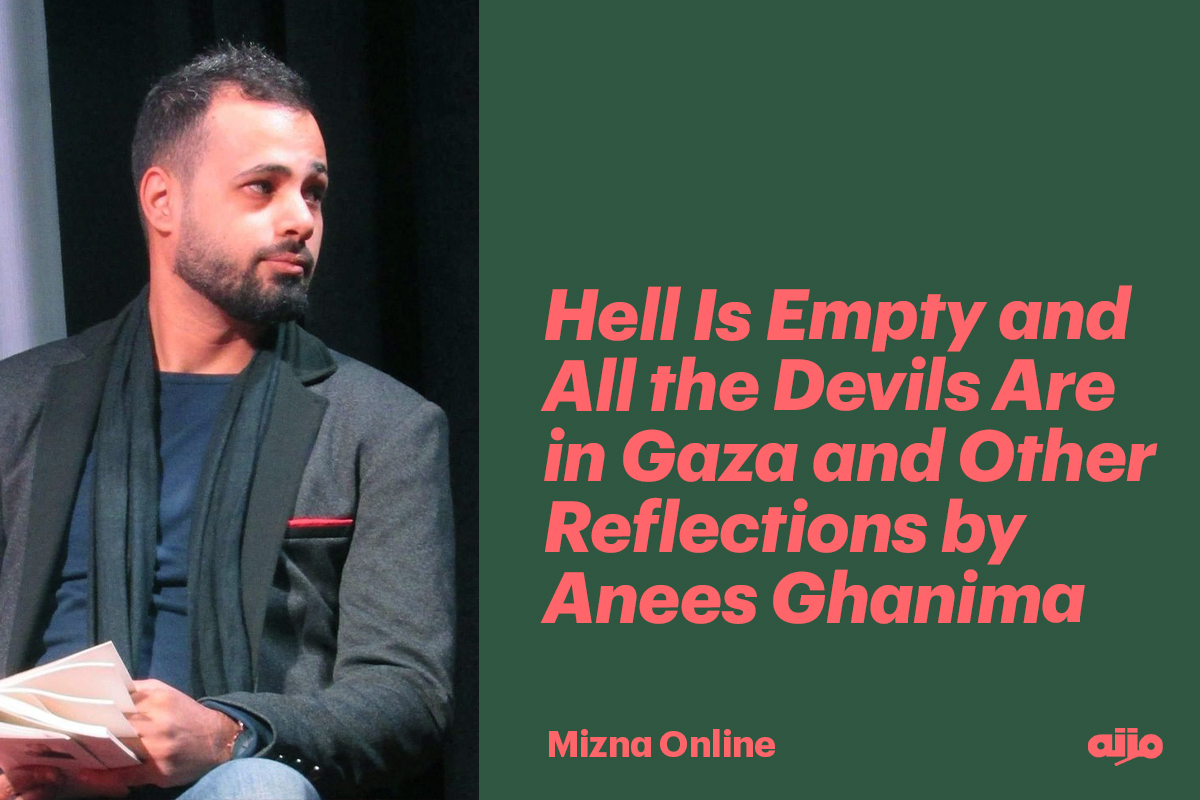

Hell Is Empty and All the Devils Are in Gaza and Other Reflections

trans. by Lena Khalaf Tuffaha

Mizna features two prose texts composed by Palestinian writer Anees Ghanima, who is currently in Gaza, displaced from his home. In the context of a media environment underscored by institutional complicity toward—indeed, at times active participation in—the ongoing genocide in Gaza, and in light of the open adoption of multiple mediatic techniques designed to misguide, obfuscate, and propagandize on behalf of colonization, the movement for Palestinian liberation has found critical sustenance and stability in radical acts of witnessing. We note, as others have done, that the Arabic word for martyr (shaheed) and witness (shaahid) share a common root. In the two texts that follow—“Hell Is Empty and All the Devils Are in Gaza” as well as “Searching for a Chocolate Bar in Gaza During the War”— Ghanima joins Motaz Azaiza, Plestia Alaqad, and Bisan Owda, among others, in enacting testimonial resistance by circumvention. Bypassing the transnational media conglomerate, the newscaster, and the editor-in-chief, Anees’s voice testifies to us directly, inviting us to follow him, to witness Gaza as he witnesses it, to watch him search for chocolate, to believe the evidence of our own eyes and ears.

—Nour Eldin H., Mizna editor

The shopkeeper’s eyebrows were raised—not so much in disbelief, it was just the way he looked, the way God made him.

People are dying and you’re here looking for a chocolate bar. You’re weird.

No, you don’t understand, sir. Come close, let me explain: I want it for my mom, and I want it bitter, too.

—Anees Ghanima

I. Hell Is Empty and All the Devils Are in Gaza

Come scream with me!

My voice is wounded.

Hello from Gaza, Gaza which cannot be enchained no matter how strong the shackles. This is a message from between piles of corpses. This is a rushed message, because we don’t have much time, even though we’re not doing anything.

Today, a month and a half will have passed—we no longer count the days—since the decision to execute this good and defiant city, simply because someone yelled loud enough to be heard, and awakened all the devils in hell. Someone in the market informs me, today is the 45th day that we’ve been under the whip of the greatest live-streamed war crime in history. Despite words’ capacity to convey cruelty, all our vocabularies are insufficient to express the enormity of what is taking place: we are all dead, even if we escape, from one day to the next, among the corpses,in a grave that cannot fit us all.

This vocabulary is also crushed, maybe to go along with the general state of public shame, wherein facts are turned upside down and the situation is reduced to its most limited outline: a humanitarian crisis—just provide them with food and medicine.

To borrow Albert Einstein’s saying: the world will not be destroyed by those who do the work of devils, but by those who sit by and watch and do not intervene.

Hey, World! We aren’t just hungry. We want to stop this genocide as well! This is our first demand. We have a right to say we don’t want to be killed. And we have a right to say that the world toying with us is a waste of time. More than seventy years is enough time for anyone to understand.

The days that have passed are as crushing as the ones that remain ahead of us, and I think an overwrought description like a knife unsheathed and slaughtering is more precise than any other description. To lean into excess, it’s not an exaggeration to say that the hours of a single day feel like an entire year.

Today I took my usual walk in Maghazi refugee camp, and my feet led me to the camp market, where there are few people and even fewer things to buy. I walked until I reached Salahedin Street, the main artery that connects all the cities of the Gaza Strip, and which has been bisected by Israeli Merkava tanks commandeered by recruited mercenaries. Enormous tanks that most people are seeing for the first time, but ultimately they are part of the Israeli war machine, and to use a Gazan phrase, the asphalt of the roads won’t tolerate them.

To the right of where I stood, beneath Gaza’s sky, is my house that was bombed by warplanes, and my father’s house, and my sister’s house, and the homes of friends, neighbors, and relatives. There, where black clouds clog up the sky day and night, it looked like someone lit a flame that would never burn out, while plumes of smoke stood frozen by the horror of the scene.

On the first day of the war, we received news that one of our cousins had been killed. It was sad that we couldn’t find a way to bid him farewell. Two days later, another cousin was killed at the civil service headquarters in Tal Al Hawa. It was painful that we didn’t even find out until a few days after his burial. And two little girls, our relatives’ daughters, were killed as well. We only learned about them on the news, because we couldn’t reach anyone when communications were cut off.

Daily, we receive news of the loss of someone we know. Either they are killed, or they are trapped under rubble, waiting as death slowly drags its feet toward them. This could be someone with whom you laughed or argued—you know they are in their final moments, and in their final moments perhaps they remember you too: your laughter together, your arguments. We lose people this close to us, people too close for death to reach, and yet death arrives a few days later even as the civil defense forces finally, miraculously, pull them out from beneath the rubble.

Someone leaves and you remain. He’s hurt no one, just like you. Someone you worked with and who has confided in you many times that he can’t even stand up to anyone, his boss for example. He’s an introverted and kind person, someone who was born to be loved, someone who could cause great harm, but only to himself. He doesn’t even have the courage to look you in the eye. Do you wonder how he looked death in the eye when it arrived?

Let’s speak up together. Let’s be loud. Let’s be angry.

Together, we can be angry.

Here we are, a month and half without electricity, potable water, clean water for bathing, without enough food—the most basic of needs, is that not so? A month and half without communications or internet access, things that aren’t luxuries, they help to save lives, do you understand? A single message might be the reason someone lives.

A month and a half away from the home you know, a month and half of losing friends and family and neighbors, a month and a half, day and night, warplanes overhead with their endless bombardment, and tanks on the ground, not far away, they might reach you any minute. A month and a half of this waiting.

You wait to understand, not to die. Can it be that after all these years, you won’t even find a brother to bury you? And why, after all these years, do you find your brother’s pickaxe in your killer’s hand?

In the first days of the war, I was in the Remal neighborhood, in my family home where we all gather during times of war—frequent as they are. In the first days, I thought my home in Shejaiyya was the most dangerous place in the world, based on how things usually go. That’s where the revenge sorties usually fall, on the most defiant of all neighborhoods in the world, the neighborhood that makes war criminals salivate. But it was different this time. On the first day they bombed Palestine Towers, not far from where we are, and on the second day, without warning, they bombed the building next door to ours, and we were all terrorized as window glass shattered over our heads and shrapnel flew into our home while we were having lunch. Covered in dust, the violent bombing led us to drag our bodies outside and run between plumes of black smoke. Some of us made it to the car and headed to Maghazi camp, and the rest of us, myself among them, returned to the house to spend the night there. It was not a good night, and the barbarity of the bombings intensified.

The next day, most of our neighbors joined the displaced and began to move toward the south, because of the frequency of the bombings in western Gaza, and we went along as well. We left our doors open and took very little with us. We moved to Meghraqa for a few days, then for a few more days to Maghazi camp, including the day of the Massacre of the Displaced, and we were minutes away from being wiped out.

We returned to Gaza again, because we missed the warmth of our home. We stayed for three days; they were absolutely not good days because the ground invasion had begun and the bombardment intensified and the missiles were nearer to us. In the early morning hours of that day, we moved toward the camp again, and on to Salaheddin Street where the tanks had truly shut down the road. A family had been killed there. So we took the longer route to the camp, from Rashid Street, or the beach road. In our family car, we didn’t pass a single person on the long road, and to the right of us we saw the warships. I kept expecting a missile to hit us—I have a phobia of ships—and some of us expected a tank to suddenly attack. As for those who remained, they were sure it would be a warplane.

In the end, by a miracle of God, we arrived. At the entrance of Nuseirat camp, it felt like the whole escapade was unbelievable. I can honestly say it was the most terrifying of the days we’ve lived so far, even worse than the day of the massacre on the street behind our, in the first days we arrived at the camp, which took the lives of one hundred people.

After this journey of displacement, as we move from house to house trying to outrun the devils unleashed in Gaza now, as they have left Hell empty, I want to say that we are, every day since the day we were born, being exterminated. But let the world remember: we do not die.

II. Searching for a Chocolate Bar in Gaza During the War

My mom keeps an empty old tin of chocolates in her bedroom because she likes the way it looks. She cleans it periodically. It brings back a flood of memories and images. A big part of Palestinian women’s memories is nostalgia. It includes her old home before displacement, and her grandmother’s recipes, and the first tree in the school yard, and certainly, the first time she tasted chocolate. Trust me when I tell you, in daily conversation, it is no less than her prayers for ceasefire.

I ran around for two weeks in search of a particular dark chocolate bar with simple specifications: 60% bitterness or greater, so as not to contradict the bitterness of war in Gaza. Preferably, it would be elegant enough to offer to foreign guests. What else would we offer them? Tea and biscuits? That won’t work, son.

At vendor Q’s—a cheerful fellow—I helped to open up his shop. Good Morning—the good ones are gone and the wicked remain! We rubbed the sleep out of our eyes and went scavenging for the lost chocolate bar in a pile of merchandise that had formed as a result of nearby bombings. It wasn’t strange in the first days, for most things were still available, except my mother’s 60% bar. The man was cheerful, as I said, and he made different offers, all potentially very convincing, and he teased, How about you take two 30% chocolate bars? Funny, but also embarrassing, and I laughed with him. He unwrapped a bar and offered it to me, Please, have a taste.

We didn’t find what we wanted there, despite his best efforts, but I paid dearly for all we tasted. As they say: a bird in the hand, and ten others fly away. Delightful!

There is no rest in war, securing any needs requires days of searching. We all woke up too late to the realization that nothing is available. A few days later, guests visited us, and we didn’t offer them my mother’s favorite chocolate. They informed us that they do not drink tea. The conversation was limited to, God will compensate us. May we return. And then they left. I stopped by the coffee roastery. I had glimpsed a man there with a chocolate bar. At one point, he stood next to me, but he left in a hurry like he was running off with hidden treasure. Should I chase after him? I called out, but it was my turn in line. Where would I find him now? Anyway, he didn’t hear me. Just great.

The shopkeeper’s eyebrows were raised—not so much in disbelief, it was just the way he looked, the way God made him.

People are dying and you’re here looking for a chocolate bar. You’re weird.

No, you don’t understand, sir. Come close, let me explain: I want it for my mom, and I want it bitter, too.

I don’t understand your request!

During the war, when you ask for chocolate, don’t ask for yourself, ask on your mother’s behalf. During the war, when you ask for chocolate, ask for the bitter kind. These are important lessons that soften the blow of I just sold the last bar a few minutes ago.

I guess I was saved from an old song “The Hero Is Martyred” and received by another one “Look What He Brought With Him.” Coffee is a treasure here, too. For so many people, it is a precious treasure to which nothing in existence compares. And coffee needs a companion, especially for coffee drinkers who don’t smoke, and—you guessed it—the best companion is dark chocolate, 60% bitterness or more, so as not to contradict the bitterness of war in Gaza. Preferably, it would be elegant enough to offer to foreign guests

I went to the market in another town based on some recommendations. There were coffee shops that were open there, shops where people were buying and selling gold, and ice cream shops. It was strange. It was also uplifting. Certainly, our special request will be there, as well. The first store was empty. The second closed, the tenth . . . I was so tired. At vendor A’s store, a tall shopkeeper hovered over his shadow, his mustache thick enough for an airplane to land on. I walked around his little place, picked out some things I definitely didn’t need, and then, shyly, I asked him.

He looked down his mustache at me and said some words, words I didn’t understand.

Go on home, son. I don’t understand what you want. Actually, I don’t have what you want.

I picked out a few more unnecessary things, paid, and withdrew from the scene.

These aren’t just hard days, they are impossible. But they aren’t days for despair. They are days for hope. We ask. We beseech. We pray. We recite. We sing incantations. We resist. We butt heads. We get along. Most importantly, we act.

Next to our rental house, there’s a corner store that was open for the first time in a while. When I got home, I decided to ask there.

The shopkeeper: My son has been martyred.

I found the chocolate bar, sitting demurely on the counter. Exactly 60% bitterness. I didn’t have much to say. I set the money down and left. I gave the chocolate to my mother. I didn’t tell her the story and she has yet to unwrap the chocolate bar.

Born in Gaza City, Anees Ghanima is a poet and web programmer. He is the CEO of NormX Group for Software and enterprise resource planning and in 2017 received first place in the Young Writer of the Year Award in the Field of Poetry from the A. M. Qattan Foundation.

Lena Khalaf Tuffaha is a poet, essayist, translator, and teaching artist. Her work has appeared in the Los Angeles Review of Books,the Nation, New England Review, Michigan Quarterly Review, Mizna, and Poetry among others. She is the author of three books, Water & Salt (Red Hen), winner of the 2018 Washington State Book Award; Kaan and Her Sisters (Trio House, 2023); and Something About Living, (University of Akron, 2024), winner of the 2022 Akron Prize. Tuffaha was the curator and translator of the 2022 series Poems from Palestine in the Baffler magazine. She is the recipient of the Poetry Foundation’s John Frederick Nims Prize for her translations from Arabic of the poems of Zakaria Mohammed. You can learn more about her work at lenakhalaftuffaha.com

Toward a Free Palestine: Resources to Learn About and Act for Palestine

We are proud to present this text as part of a list of resources to take action for and learn about Palestine, as well as works by Palestinian artists, writers, activists, and cultural workers.

Support Anees and His Family: Donate to Their GoFundMe

Due to the ongoing genocide in Gaza, Anees and his family have been displaced. A GoFundMe has been set up to help alleviate some of the material losses incurred. We thank you for your support and solidarity to the contributors who make Mizna possible.