April 25, 2025

On Parallel Time

trans. by Nour Eldin Hussein

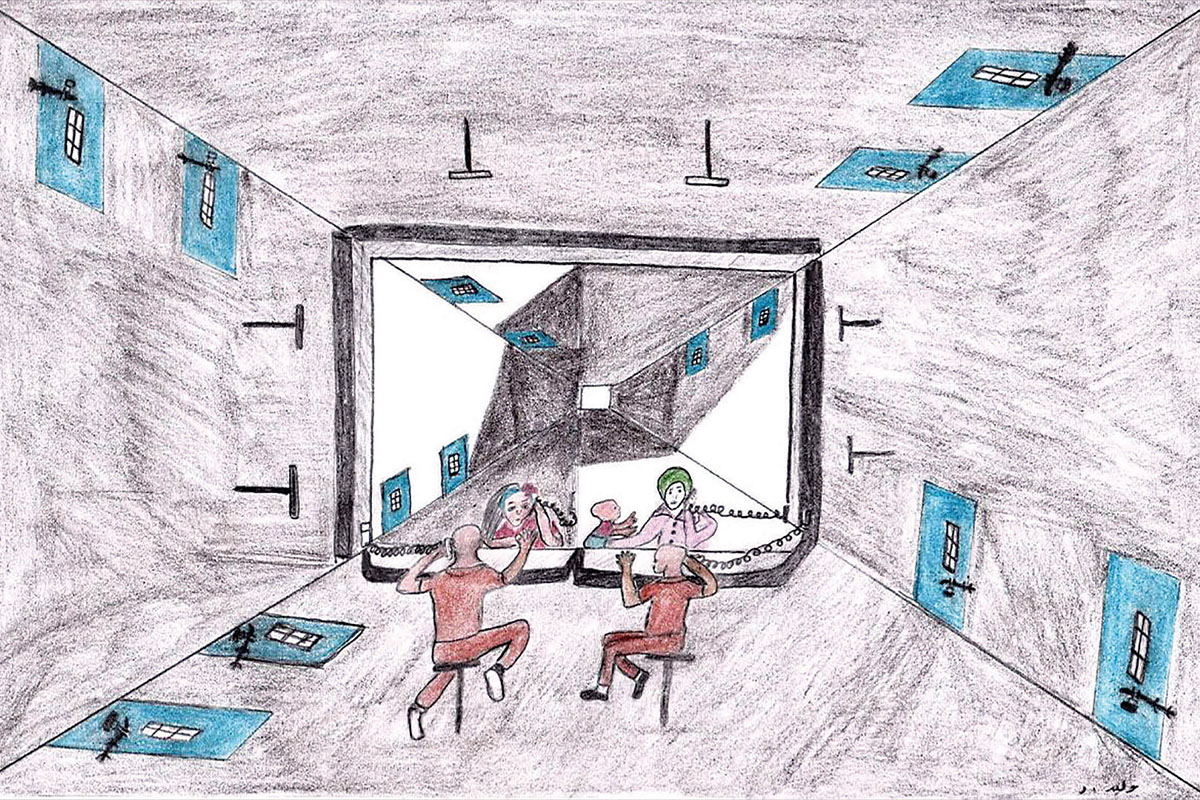

Image by Walid Daqqa, produced during his imprisonment

Thinker, freedom fighter, and political prisoner Walid Daqqa describes the systematic colonization of time in Zionist prisons in a letter to a friend. This Mizna Online exclusive feature is published as part of Mizna 25.2: Futurities, link to order HERE.

—Nour Eldin Hussein, assistant editor

We are a part of history, and history—as it is well known—is a condition and an action in the past. Except us: We are a past continuous and neverending. We address you all from it presently, so that it does not become your future.

—Walid Daqqa, trans. Nour Eldin Hussein

On Parallel Time

My dear brother, Abu Omar,1 greetings.

Today is the twenty-fifth of March, the first day of my twentieth year imprisoned. Today is also the twentieth birthday of a young comrade. Such an “occasion”—the anniversary of my imprisonment, the birth of the comrade—reminds me of a question I posed to myself: how old is Lena today, who has become a mother of two? How old is Najla, mother to three? And Hanin, mother to a girl? And Obeida—traveling to America for his studies, bidding farewell to his youth, yet without my bidding him farewell? And my brothers and sisters—either kids when I left them on the day of my arrest or born after the fact—how old are my brothers and sisters, those “children” who have since married and become mothers and fathers to kids themselves?

I had not asked this before. Time in the broad sense, how much of it passes—that had not concerned me as much as the minutes do when they would fly by during those short family visits. Too brief a time for me to lay out for them all the notes I’ve recorded on the palm of my hand; all the missions Sanaa2 will need particular effort for—not just to carry them out, but to simply remember them, as they have barred us from the use of pen or paper during our visits, and so it is only memory that remains as the sole faculty available for recollection. And so I forget to ponder the lines that have begun to dig in the face of my mother for years now, and I forget to ponder her hair that she has begun to dye with henna to hide their gray from me so that I would not inquire after her true age.

Her true age? I do not know my mother’s “true age.” My mother has two ages: her chronological age, which I do not know, and her prisonological age. Let’s say her age in that parallel time is nineteen years.

I write to you all from Parallel Time. In Parallel Time, where there is fixity of place, we do not use the standard units of your time like minutes and hours, not unless the two lines of our time and your time meet at the visitation window, whereupon we are forced to interact with your chronological formulae. It is, anyway, the only thing that has not changed in your time and that we still remember how to use.

It has reached me on the tongue of the young delegates of the intifada—indeed, this was told to me personally—that many things have changed in your time. The phone no longer has a rotary dial, no longer works via coin slot but requires credit to activate; and also that the frames of car tires do not have another inner, internal structure, but are tubeless.

I was quite impressed by such a system! One where the tire is made of a material that closes in on itself, plugging up any holes spontaneously and immediately, stopping any air from leaking out of it. I’m quite impressed, as it seems to resemble the prisoner who resists the tacks laid down by the prison guards by way of that self-contained system—the tubeless system. Generally, there is no escape for the prisoner save for relying on such a self-correcting regime, as our driver or drivers cannot see a tack on the road except that they drive over it or a bump in the road except that they trip on it, supposing that they are taking a short cut—shortening the distance, reducing the effort. It’s not just that our drivers have been reckless, they have simply been relying on that inner tube as if it’s not made of flesh and blood—as if there is no end, no goal. Until we become like cash passed around on the market, the market of political maneuvers:

“Take this tire and permit us some of the vehicle.”

Of what value is the tire without the vehicle?

I do wish for the Palestinian and Arab leadership to improve. I do wish for our people and for their political power to take up such an internal, self-reparatory system without having to resort to those who call themselves “roadside assistance”—the Americans and their ilk who today corrupt all the earth in Lebanon. And if it is unavoidable to speak of politics—despite the fact that I have decided, today especially, not to speak of politics—then we, in Parallel Time, see you, while you all do not see us. We hear you all while you all do not hear us. As if glass, tinted just on your side, stands between us, like the kind for cars carrying important people such that some of us behave arrogantly as if they are, in fact, an important person. They have convinced us that we are important people.

And why not! The prestige of the situation calls for it. In all the world, there are states and governments who have prisoners except for us: We are prisoners who have a ministry in a government that does not have a state!3

We—for those who do not know—have dwelled here in Parallel Time since before the end of the Cold War and the collapse of the Soviet Union and the communist bloc, before the fall of the Berlin Wall and the First and Second and Third Gulf wars, before Madrid and Oslo and before the eruptions of the First and Second intifadas. In Parallel Time we are as old as that revolution and we precede the genesis of some of its factions; we precede the Arabic satellite channels and the proliferation of the culture of hamburgers in our capitals. Indeed, we are before the invention of mobile phones and the propagation of those new telecommunications systems and the internet. We are a part of history, and history—as it is well known—is a condition and an action in the past. Except us: We are a past continuous and neverending. We address you all from it presently, so that it does not become your future.

I have said that, here, our time is not your time. Our time does not proceed on the axis of past and present and future; our time that flows in the fixity of place ousts from our language typical concepts of time and place—or say that it confuses them, according to your standards. We do not ask “when?” or “where shall we meet?” for example, rather we have already met and still meet at the same place. We proceed here flexibly to and fro on the axis of past and present, and every moment after this present one is an unknown future that we are no longer capable of interacting with. Of no control to us is our future—a condition quite similar to that of all the Arab peoples, with the fundamental difference that our occupation is foreign and their jailers Arab; here we’re imprisoned for searching for the future, and there the future is buried alive.

In our Parallel Time, most of us haven’t given an answer to that question posed usually to children: What do you want to be when you grow up? I, even now—even though I am forty-four years old—have no idea what I would like to be when I grow up!

If it is the case that time as a concept is inherent to matter—if it is its moving aspect—and if place is the fixity of matter, then we in Parallel Time have come to represent the units of that time. We are the time that wrestles with place and in a state of internal contradiction with it. We have become units of time. We have come to define points on the axis of time by the arrest of so-and-so, the arrival to the prison of such-and-such or their release from it. Such things are important chronological events for lives in Parallel Time. We know how to define the hour and the day and history by your units of time, but they are units that go unused; what is used is: X happened on the day so-and-so came, or before or after such-and-such was liberated. And because we do not know when so-and-so will be arrested in the future or when they will be moved from one prison to another, we have nothing by which to define a future event. So, when we talk of the future, we borrow your chronological units.

Your time is the true time. Your time is the time of the future.

In Parallel Time and in the controversy of the relationship between us and place, we develop relations with objects that are strange; relationships that nobody besides those imprisoned in Parallel Time would understand. How is it possible to understand the emotional relationship between a prisoner and the undershirt that was the thing he was wearing the moment before his arrest? How is it possible to explain the depth of our relationships with predefined objects, the loss of which may lead to sorrow and even weeping. Things like a certain lighter or a specific box of cigarettes acquire deep emotional significance because of their distinction as the last thing we had in the “future,” as if they affirm that we, one day, had been outside of Parallel Time—proof of our membership to your time. Such objects are not simply consumable materials to be thrown in the trash following their use: they are the drowning man’s last life preserver in the ocean of Parallel Time.

In the year 1996, I heard the honk of a Subaru for the first time in ten years and I wept. In our time, a car horn is used for more than simply alerting passersby; in our time, a car horn is liable to stir the deepest of human emotions.

Through their relationship with place, the people of Parallel Time develop relationships no stranger than those with objects. There you are suddenly, developing a special relationship with specks on the ceiling of your cell brought about by leaking water and the humidity. Or you might develop a relationship with a hole or crack in the door. Who would understand that dialogue replete with fervor, with emotion, with interruption and description as if it were a conversation on the topic of heaven and its door and not on the cell and its holes?

The first prisoner: “There’s nothing better than department four . . . Oh, to be back in the days of department four . . .”

The second prisoner: “Sure, but the best thing about department four was cell seven.”

The first prisoner—expelling all the air from his lungs in heartbreak over those days—interrupts: “I know, I know, but what can you say? From this cell you can hear the precise crack of dawn—the sound of cars on the highway.”

The second prisoner, also interrupting: “But that’s not it—you know the cell door? Between the cell door and the wall, right at the hinges, is an entire two centimeter-crack so wide you can see through it while lying in bed. You can see through to the ends of the earth.”

The first prisoner: “Man, why are you saying this? Department four is the best.”

How simple the dreams, how great the human, how small the place, how grand the idea.

I did not plan to write on a day like today—not about time, nor about place, nor about our Parallel Time, nor about anything: not about politics, not about philosophy. I actually had an inclination to write about what worries me—what I love and what I hate—but my unplanned writing resembles my unplanned life. I will even admit that I have never planned for anything: not to be a resistance fighter, nor a member of a political party or faction, nor even to participate in politics—not because all that is a mistake and not because politics is an objectionable, detestable matter as some like to see it—but because, in my view, they are huge and complicated topics. I am not a politician nor a resistance fighter despite previous insistence and observation. I very simply could have continued my life as a house painter or gas station worker as I was up until the moment of my arrest. I could have married one of my cousins early as many do, and she could have borne seven or ten kids; and I would have bought a truck and learned the business of car dealing and the going rates of hard currency. All of that was possible, until I saw what I saw of the atrocities during the Lebanon War and the massacres that followed it—Sabra, Shatila. It inspired in my being shock and astonishment.

To stop feeling shock and astonishment, to stop feeling the misery of people (any people), the blunting of emotion before scenes of atrocity (any atrocity), was, in my view, a daily anxiety, and the measure of the extent of my steadfastness and solidity. To feel for people and the pain of humanity is the very core of civilization. The intellectual core of the human being is intention; the corporeal core is work; and the spiritual core is feeling—to feel for people and the pain of humanity is the core of human civilization.

It is this core especially that is targeted in the life of the prisoner every hour of every day of every year. You are not targeted as a political subject in the first degree, neither are you targeted as a religious subject, nor are you targeted as a consumerist subject to be punished by deprivation from the pleasures of material life. You may adopt whatever political conviction suits you, and you may practice whatever religious observance, and you may even be provided with much of your material needs—but it remains that the targeted entity of the first degree is the social, human entity within you.

What is targeted is any relationship outside of the self, any relationship you value with other people, with nature—even your relationship with the jailer as a human being. Truly, they do it all to push you to hate. What is targeted is love, your sense of beauty, your sense of humanity.

I profess now, in my twentieth year of imprisonment, that I am still no good at the hatred, nor the crudeness, nor the coarseness that life in prison imposes. I profess now that I still rejoice at the barest of things with the glee of small children. I am still filled with delight at a kind word of encouragement or compliment. I profess that my heart skips a beat at the sight of a flower on the television, at a scene of nature, at the sea. I profess that I am joyous despite it all, and I yearn not for any pleasure of the many pleasures of the world save for two: the sight of children, sent off from all corners of the village to their schools; and the sight of workers in the early hours of the morning as they proceed from the alleys of the neighborhoods in a dusty, wintry morning, toward the town square—vital, prepared to travel to their place of work. And I profess now that all these feelings, all this love, would not have remained if not for the sole and solitary love of my mother, the love of Sanaa and my brother Hosny, the support of my people and my dearest friends who surround me on all sides—I to them, and they to me.

I profess that I am still a human being holding onto his love as if it were a flaming torch. And I will remain steadfast in that love—I will continue to love you all, for it is love and love only that remains my sole victory over my jailers.

With regards, Milad.

- 1.

Refers to Palestinian political science scholar Azmi Bishara. This letter was sent from Daqqa to Bishara in 2005 and is translated and published here with permission, with special thanks to assistance from Mazher Al-Zoby. Ed .

↩︎ - 2. Refers to the journalist and activist Sanaa Salameh who was married to Daqqa. Ed .

↩︎ - 3. Refers to the Palestinian Authority’s Ministry of Detainees and Ex-Detainees Affairs. Ed . ↩︎

Translator’s note: Born in 1961 in the town of Baqa Al-Gharbiyyah in occupied Palestine, Walid Daqqa was a Palestinian philosopher, political theorist, playwright, and armed resistance fighter. Despite evidence to the contrary, Daqqa was accused, charged, and convicted of involvement in a 1984 PFLP operation that captured and killed an Israeli soldier, for which he was sentenced to life by the Zionist entity in 1986 and subsequently languished, imprisoned until his death on April 7, 2024 (al-Shaikh 2021a, 276). The text presented here was penned in 2005 in Gilboa Prison, on the first day of his twentieth year behind bars.

Despite his captivity, Daqqa remained politically active. As hinted here, he maintained regular contact with the cultural intelligentsia in colonized Palestine, enabling him to conduct a lively political life from within. Notably, Daqqa served as a member of the political party Democratic National Rally and headed the Palestinian Prisoners’ Movement.

Perhaps the most significant of Daqqa’s activities in this respect are his intellectual pursuits, for which his comrades in captivity nicknamed him the Prince of Culture, Amir al-Thaqafah. Pursuing and successfully graduating with an M.A in political science, Daqqa produced a prolific—and largely untranslated—intellectual output that was transdisciplinary in form, taking the shape of screenplays, musicals, novels, nonfiction memoir, children’s books, and works of political and philosophical theory. Situated in the context of a post-Oslo status quo, his body of work proceeds from the urgencies marked by the transmutation of the PLO into the PA, the subsequent official renunciation of armed resistance as a political method, and the “dis-memberment” of the 1948 Palestinians from the national body (ibid., 274). In particular, Daqqa’s intellectual concerns revolve around the peculiar ontology of the post-Oslo Palestinian, a subject who is increasingly forced to exist in a state of a prospectless, futureless infinite present—the parallel time of Palestinian political existence. The text presented here is an early but foundational instantiation of this central intellectual project.

Daqqa leaves behind a legacy that demands dogged belief in a willful, agentic future. Indeed, at every turn Daqqa refused to capitulate to that hallucination of the infinite present induced by the apartheid state. In 1996, an imprisoned Daqqa met and became involved with journalist and translator Sana Salama. Though initially blocked by the Zionist entity, the two married after the intervention of Azmi Bishara—the addressee of the letter translated here and a member of the Knesset at the time—in 1999. Save for exceptional instances like their wedding and a single incident in which Sana managed to steal a hug in 2015 (ibid., 280) the couple conducted the entirety of their marital relationship separated by the steel of prison bars. The couple conceived via liberated seed, nutfah muharrarah, and Milad—birth in Arabic—was born on February 3, 2020 (al-Shaikh 2021b, 84-5). As in other texts, Daqqa concludes his 2005 letter to Azmi Bishara by hailing his future child: Ma’ tahiyyati, Milad.

—Nour Eldin Hussein

References:

- 1. Al-Shaikh, Abdul-Rahim. 2021a. “Al-Zaman Al-Muwazi Fi Fikr Walid Daqqa [Parallel Time in the Thought of Walid Daqqa].” المجلة العربية للعلوم الإنسانية. 39 (155): 271–308. https://doi.org/10.34120/ajh.v39i155.2889.

- 2. Al-Shaikh, Abdul-Rahim. 2021b. “The Parallel Human: Walid Daqqah on the 1948 Palestinian Political Prisoners.” Confluences Méditerranée N° 117 (2): 73–87. https://doi.org/10.3917/come.117.0075.

Walid Daqqa (July 18, 1961–April 7, 2024) was a Palestinian philosopher, political theorist, author, and armed resistance fighter who was imprisoned for thirty-eight years, the longest serving Palestinian prisoner in Israeli jails. From prison, he wrote a number of books including, The Tale of the Secrets of Oil, Fusion of Consciousness, and A Parallel Time. Daqqa died in prison, succumbing to a rare form of bone cancer which was exacerbated by medical negligence and torture of the Israeli Prison Service. He has not been given a proper burial as his body continues to be retained by the Security Cabinet of Israel at the time of this publication.

Nour Eldin Hussein is an Egyptian essayist, researcher, translator, editor, and enthusiast of the written and spoken word. He holds an M.A in Arab media and culture studies, and he lives, works, and studies in Minneapolis, MN where he serves as assistant editor for Mizna. He maintains lightedroom, a small blog on Substack where he writes about digital culture, life online, and the Arab world among others.