May 22, 2025

Four Poems

trans. Sara Elkamel

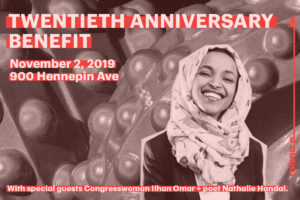

Translated by Sara Elkamel, Palestinian poet and playwright Dalia Taha builds a refuge for a poetry exhausted after millennia-long encounters with pain and conflict. Special courtesy to The Dial, where the poems “Enter Wrist Pain” and “Enter Poem” were originally published .

—Nour Eldin H., assistant editor

Protect the head, where the algae grow,

and the sun screams from the summit.

The head that has stared for centuries

into the sea as it closed its eyelids,

and never blinked.

—Dalia Taha, trans. Sara Elkamel

Enter Writing

I would like to thank books. Magazines, articles,

poems, even the advice column, and the arts and culture section.

Thank you to philosophy books,

and dictionaries too; massive and silent, as though apologizing

for the work they’re trying to do.

I would like to thank words.

When we put them side by side, they become declarations of love

or war, and everything that falls in between:

poems.

Thank you to the pamphlets and leaflets, exchanged in secret,

that have shaken kingdoms;

to the newspapers printed clandestinely in dark rooms, before blowing up the world.

To speeches written in sweltering, overcrowded rooms, to letters smuggled out of prisons,

and to words scribbled into the margins by faint light.

Thank you to the first word a child draws; broken and distorted, like a puzzle piece.

Thank you to cave paintings—these letters from another world. To the memoirs

of death-row prisoners,

and the words teenagers inscribe inside abandoned houses.

Thank you to the sheets of worker signatures stitched together into a roll so massive,

the Parliament’s doorframe had to be excised to let it through. And thank you to graffiti,

flashing brighter than billboards, in cities that devour their residents.

Thank you to writing under genocide.

Enter Poetry

Like men and women,

poetry must shield its head with its hands in times of war.

Take the bullet to the foot,

or to the hand.

And answer “Yes, I can,” just as Akhmatova answered

when in the queue outside the prison in Leningrad,

a woman whispered: “Can you describe this?”

But make sure to protect poetry’s head.

Protect the head, where the algae grow,

and the sun screams from the summit.

The head that has stared for centuries

into the sea as it closed its eyelids,

and never blinked.

Only then can you transmute

your sorrow into an idea,

and hand it over like trees

bequeath their shade to the walls and the sidewalks.

Poetry must keep eternity

from slipping through its fingers;

it should carry its bite mark shamelessly on its neck.

Poetry should run around with nothing but a head,

two crazy eyes,

a love bite,

and Akhmatova’s answer.

Enter Poem*

The last poem you read

On your phone

Its light cast across your face

Standing up

On the bus from Jerusalem

Leaning against the door

Your bag between your feet

The phone in your hands

The poem you’re thinking about right now

Crossing Manarah Square

Your hands in your pockets

Your scarf obscuring half your face

The poem you read first thing in the morning

Before fully waking up

Before the world assaulted you

The poem you read in bed

During the second intifada

While the tanks besieged the Muqataá

When you knew very little about the world

The poem you read on a hot summer

In a strange city

Where you spoke to no one

The poem you read while reading another book

The poem you read on your mattress after your cellmates had gone to sleep

The poem that knows something you do not yet know about yourself

The poem you don’t fully remember

But remember walking in Nablus after reading it

How the world seemed then

A mystery

The poem you read during the war

And though it did not comfort you

It did, for a few moments, distract you

The poem you found wearily flipping through a book

At your friend’s house

Because you had nothing to say

The poem your grandfather kept reciting even after he lost his mind

The poem you read thousands of times

The poem you wanted to share with everyone you know

The poem you are thinking of right now

Crossing Manarah Square

Your hands in your pockets

Your scarf obscuring half your face

Suddenly

You are captivated by the trees

And you don’t know where you’re going

Like the frost

Drifting and alone

With every step

You swallow the fog

Enter Wrist Pain*

While people were dying in the thousands during the Black Plague, Petrarch, a thirteenth century poet, prowled monastery cellars looking for ancient manuscripts that had stayed silent for hundreds of years. When he came across a manuscript by Cicero, a Roman poet, he copied it for weeks on end until his wrist ached. I will be thinking of this as I cross the Container checkpoint, as the soldiers construct roads and erect fences, littering our hills with bulldozers. I will be thinking of how Petrarch’s trivial wrist pain has traversed centuries, like a bulldozer, only because he turned it into a sentence on a page. And that’s why this image of a scribe, copying a book in full—to give to dwellers of the centuries to come—as a plague races people to the villages they have fled to, will always remain my idea of the road. And that wrist pain will be the bulldozer I scatter over the hills—the hills above which soot continues to rise.

والآن، تعالَيْ أيَّتُها الكِتابَة

شُكراً للكُتب؛ للمجلّات، المقالات

للقصائدِ، حتى عامودِ النّصائح، وقِسمِ الأخبارِ الفنّيَّة

شُكراً لكُتُب الفلسفة

للقواميسِ أيضاً، ضخمةً وصامتةً

كأنَّها تعتذِرُ عمّا تُحاوِلُ أن تقومَ به

شُكراً للكلِماتِ، نضعُها جنباً إلى جنبٍ وتصيرُ إعلاناً عن الحُبّ،

تهديداً بالحرب، وما بينهُما: قصائد

شكراً للكُتيِّباتِ، والمناشيرِ التي تبادَلَها الناسُ بالسِّر

وهزَّتْ ممالكَ

للجرائدِ التي طُبِعَت بِصَمتٍ في غُرَفٍ مُعتِمة، قبل أن تُفجِّرَ العالَم

للبياناتِ التي كُتِبَت في غُرفٍ مُكتَظَّةٍ ودَبِقَة، للرسائلِ المُهَرَّبَةِ من السُّجون

لما كُتِبَ في الليلِ على ضَوْءٍ خافِتٍ في هوامشِ الكُتُب

شُكراً للكَلِمةِ الأُولى التي يَخُطّها الأطفالُ، مُكَسَّرةً، ومُتعرِّجةً، كأنَّها أُحْجِية. ولآخِرِ كَلِمةٍ

يَكتُبُها المرءُ، مِثلَ آخر وَرَقَة على الأغصانِ الباردة

شُكراً للنُّقوشِ على الحِجارة، رسائلَ مِن عالَمٍ آخَر

لمُذكِّراتِ المَحكومينَ بالإعدام

لما خَطَّهُ المُراهقونَ في البُيوتِ المَهجورة

للعرائضِ التي حَمَلَت تواقيعَ العُمّال، تلك التي أزالوا إطارَ بابِ البرلمانِ حتّى يُدخلوها

شُكراً للكتاباتِ على الجُدرانِ في مُدُنٍ تفترِسُ سُكّانَها:

مُتوهِّجةً أكثرَ مِن لَوحاتِ الاعلاناتِ التّجاريَّة

شكراً للكتَابَةِ تَحْتَ الإبَادَةِ.

ولا أعرفُ، لا أعرفُ، كيف يُحاولُ أحدٌ أن يوقِفَ الجريمةَ بأن يُعيدَ الدُّموعَ إلى أصحابِها. العدالةُ لَيسَت أنْ نَرسِمَ الدُّموعَ على صناديقِ الشَّحن. العدالةُ أن تُغرِقَ صناديقُ الشَّحنِ السفينةَ، أن تَكسِرَ رُفوفَ المكتبات.

والآن، تعالَ أيُّها الشِّعرُ

مثلَ البشَرِ

على الشِّعرِ أن يُغَطِّيَ رأسَهُ بِيَدَيْهِ في الحَرب.

خُذ الطَّلقةَ في القدَمِ

أو اليَدِ.

وأجِبْ ”نعَم، أستطيعُ“ كما أجابَتْ أخماتوفا

حينَ وَقَفَت في طَابُورٍ أمامَ سِجْنٍ في ليننغرَاد

وهَمَسَت امرَأةٌ هل ”تَستَطيعينَ أنْ تَصِفي هذا“؟

ولكنِ احْمِ رأسَ الشِّعرِ

احمِ رأسَهُ التي تَنمو عليها الطَّحالِب

وتصرخُ الشَّمسُ على سَطحِها.

رأسَهُ التي منذُ قُرونٍ تُحدِّقُ بالبَحرِ وهو يُغلقُ أجفانَهُ

دونَ أن تَرمِش.

هناكَ تستطيعُ أن تُحَوِّلَ

حُزنَكَ إلى فِكرةٍ

وتمنَحَهُ للآخَرين كما تمنحُ الأشجارُ

ظِلالَها للجُدرانِ والأرصفَة.

على الشِّعرِ ألّا يُفلِتَ الأبَديَّةَ من يَدِهِ

أن يحمِلَ عَضَّتَها على رَقَبَتِهِ بِلا خَجَل.

أصلاً على الشِّعرِ أن يَعدُوَ برأسٍ فقَط

وعَينَيْنِ مَجنونَتَيْنِ

وعَضَّةِ الحُب

وإجابةِ أخماتوفا

والآن، تعالَيْ أيَّتُها القَصيدة

القصيدةُ الأخيرةُ التي قرأتِها على هاتِفِكِ المَحمولِ

-وضَوْؤُهُ يُنيرُ وجهَكِ-

في الباصِ القادمِ من القُدسِ

واقفةً، تستَنِدينَ على البابِ

حقيبتُكِ بينَ قَدَمَيْكِ،

وهاتِفُكِ في يَدِك

القصيدةُ التي تُفكّرينَ بِها الآنَ

وأنتِ تقطَعينَ دُوّارَ المَنارة

يداكِ في جَيبَتَيكِ

ولَفحتُكِ تُغطّي نِصفَ وَجهِكِ

القصيدةُ التي قرأتِها أولَ شَيءٍ في الصباحِ قبلَ أن تستَيقِظي تماماً

قبلَ أن يُهاجِمَكِ العالَم

القصيدةُ التي قرأتِها في سَريرِكِ في الانتفاضَةِ الثانِية

بينَما الدَّبّاباتُ تُحاصِرُ المُقاطَعة

وأنتِ لا تعرفينَ شيئاً عن العالَمِ بَعد

القصيدةُ التي قرأتِها في صَيْفٍ حارٍّ

في مدينةٍ غريبةٍ لم تتعرَّفي فيها على أحد

القصيدةُ التي قرأتِها وأنتِ تقرَئينَ كتاباً آخَر

القصيدةُ التي قرأتِها على بُرشِكِ في الليلِ بعد أن نامَ جميعُ الأسرى

القصيدةُ التي تعرِفُ شيئاً لا تعرفينَهُ بَعدُ عن نفسِك

القصيدةُ التي لا تذكُرينَها تماماً ولكنَّكِ تذكُرينَ كيفَ مَشَيْتِ في نابُلْسَ بَعدَها

وكأنَّ العالَمَ سِرٌّ هائِل

القصيدةُ التي قرأتِها في الحَربِ

ولم تُواسِكِ ولكنَّها شتَّتَت انتباهَكِ للَحْظات

القصيدةُ التي وجدتِها وأنتِ تتَصَفَّحينَ بِمَللٍ كتاباً في بيتِ أصدقائِكِ

لأنكِ لا تجِدينَ ما ستقولينَه

القصيدةُ التي ظَلَّ جَدُّكِ يُردِّدُها حتى بعدَ أن فقَدَ عقلَه

القصيدةُ التي قرأتِها آلافَ المرّات

القصيدةُ التي أردتِ أن تُشارِكيها معَ كُلِّ شَخصٍ تعرفينَهُ

القصيدةُ التي تُفكِّرينَ بها الآنَ

وأنتِ تقطعينَ دُوّارَ المَنارَةِ

يداكِ في جيبتَيْكِ

ولفحتُكِ تُغطّي نِصْفَ وَجْهِكِ

تستَوْقِفُكِ الأشجارُ

ولا تعرفينَ أينَ ستَذْهَبينَ

تُشْبِهينَ الصَّقيعَ

هائِمةً ووحيدةً

تَمشينَ وتَشرَبين الضَّباب.

والآن، تعالَ أيُّها الوجَعُ في الرُّسْغ

بينَما كانت الناسُ تهلَكُ بالآلافِ في الطّاعونِ الأسوَدِ، كانَ هناكَ في القرنِ الثالثَ عشَرَ شاعِرٌ، بترارك، يدورُ مِن قَبْوِ دَيْرٍ إلى قَبْوِ دَيْرٍ، يبحثُ عن المخطوطاتِ القديمةِ التي ظلَّت صامتةً لمِئاتِ السِّنين. حين وجَدَ مخطوطةً لسسيرو، شاعرٍ روماني، ظَلَّ ينسخُها لأسابيعَ حتّى أوجعَهُ رُسْغُه. وسيكونُ ذلك ما أفكِّرُ به وأنا أعبُرُ حاجِزَ الكونتينر بَيْنَ رَامَ الله وَبَيتِ لَحْم بينما يشُقُّ المستعمِرونَ الطُّرُقَ، ويبنونَ الأسوارَ، وينشُرونَ الجرّافاتِ في تِلالِنا. كيفَ ظلَّ ذلكَ الوجَعُ الصغيرُ في الرُّسغِ يعبُرُ مثلَ جرّافةٍ من قَرْنٍ إلى قَرنٍ كما الكتابِ الذي أنقذَهُ فقَط لأنَّهُ صارَ جُملةً على صفحةٍ. ولهذا، ستظلُّ هذهِ الصّورةُ لِمَن ينسَخُ كتاباً كامِلاً -حتّى يُهدِيَهُ لِمَن سيَمشونَ على هذا الكَوكَبِ في القُرونِ القادمة- بينما كانَ الطاعونُ يسبِقُ الناسَ إلى القُرى التي يلجؤونَ إليها هي فِكرَتي عن الطّريق، وسيكونُ ذلكَ الوجَعُ في الرُّسغِ جرّافاتي التي أنشُرُها في التّلال، التلالِ التي يتصاعَدُ مِنها الغُبار.

Dalia Taha is a Palestinian poet, playwright, and educator. She was awarded the 2024 Banipal Visiting Author Fellowship, and the 2025 Norwegian Writers Guild solidarity award. Taha has published three poetry books, a novel, two plays, and a children poetry book. Her plays have been staged at the Royal Court Theatre in London and the Flemish Royal Theatre in Brussels, among others. Her forthcoming poetry collection, Enter World, will be published in 2025 by Almutawassit Publishing House, and in English translation in 2026 by Graywolf Press. Taha taught at Brown University, Ramallah Drama Academy, Birzeit University and Al-Quds Bard University. She lives in Ramallah.

Sara Elkamel holds an MA in arts journalism from Columbia University and an MFA in poetry from New York University. A Pushcart Prize winner, she is the author of the poetry chapbook Field of No Justice (African Poetry Book Fund & Akashic Books, 2021). Her translations include Mona Kareem’s chapbook, I Will Not Fold These Maps (Poetry Translation Centre, 2023) and Dalia Taha’s collection of poetry, Enter World (Graywolf Press, 2026).