Life must be disrupted in order to be revealed: The Recording as Record and the Hyper-Surveilled Entity Not Meant to Exist in An Unusual Summer

Lamia Abukhadra

This text is presented as part of the Mizna Film Series, a monthly selection which expands our regular film programming to include screenings, critical essays, filmmaker interviews, and discussions exploring revolutionary forms of cinema from the SWANA region and beyond.

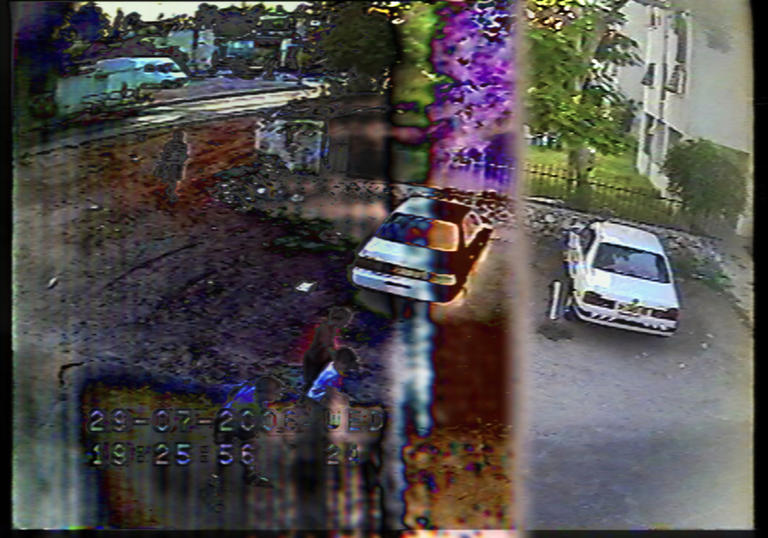

On two separate occasions in Kamal Aljafari’s An Unusual Summer, a child’s voice, the only audible one in the film, says, “منشفش ولا شي، اه و كتير أشياء” which is subtitled as “we cannot see anything, and a lot of things.” Though seemingly insignificant, this phrase captures the formal and narrative interventions Aljafari employs to surveillance footage that his father took of their neighborhood, inserting nuance and emotion to “plotless acts”1 and subverting the images and perceptions produced by surveillance technologies. The surveillance image is static, detached and matter-of-fact. In purporting to offer a totalizing view, it makes the bodies captured by its infrastructures anonymous and inhuman: a group of moving pixels or the signals sent to magnetic particles on a video tape. The utterance also alludes to the sociopolitical context of surveillance in Occupied Palestine and its paradoxical consequences towards the Palestinian body. Those who are racialized by the occupying state, Palestinians, are surveilled, controlled, and suppressed in order to erase them physically and imaginally and to further the settler colonial project, creating a paradox of the hyper-surveilled body that is not meant to exist.

An Unusual Summer is a film based on found footage. In 2006, Abdeljalil Aljafari, Kamal’s father, decided to install a surveillance camera outside of his house to figure out who kept breaking his car window. Years later, after Abdeljalil had passed away, Kamal’s sister found the tapes. The material was like a treasure trove, allowing the filmmaker to share in the quotidian life of Al Ramle once again.2 Considered by Kamal Aljafari to be a collaboration with his late father, the film consists of surveillance footage fixed on the alleyway behind their house. On the left side of the frame is a busy road, near the top right is a grassy area with a tree, and in the center of the frame sit the family cars. Neighbors walk by. The Aljafari family members go to work or to the bakery. Daily life passes, all recorded by the camera.

When watching the film, one quickly forgets about the “plot,” finding the culprit behind the broken car window. This is not because the culprit is unimportant but because the editorial and narrative elements Aljafari implements make each figure equally important. Slowly, through Aljafari’s interventions, we are introduced to the figures who cross the frame as “characters,” and we learn them through their movements. Abu Rizeq trips because he had an accident when he was young; George Sousou is always wearing a blue shirt; the Imses sisters are dressmakers and are never seen apart; a man is in love with Aljafari’s sister and brings a bouquet to the house; Abou Ghazaleh is always on his bike, whistling––he is never seen on foot; a white cat; the tree; children playing with a kite; the kite itself.

The way each character appears is choreographed and repetitive; the frame becomes a stage. The footage from the found tapes was silent, but Aljafari has added sound, much of which he recorded from the same position where the surveillance camera had been installed. The effect is the creation of atmosphere, intimacy, and humor. A nylon bag dances across the gravel lot, crinkling, and the camera follows it. A gust of wind, caught on camera as a swirl of dust moving from right to left. Aljafari zooms in and follows the swirl, repeating the gesture a few times. Every day, at 5:13 am, a man in a checkered shirt walks across the lot to catch a bus. Aljafari layers multiple instances of the man’s routine on top of one another so that he is walking with his many selves, over and over. Ah Law Abeltak Men Zaman (اه لو أبلتك من زمان) by Warda plays, and the superimpositions become dancers in the early morning light. When Abdeljalil Aljafari coughs on camera, we actually hear Kamal coughing; a son filling in the familiar utterances of his deceased father. An old man always touches the trunks of the cars he passes, gravel crunching beneath his feet. Around minute twenty-six, we see him do it again, but this time a title card says, “He is tired.” Something so intimate: to be so familiar with the body language of your neighbor so that you know that he is experiencing fatigue even through the surveillance footage. Such attention to detail, such care, is not possible within apparatuses of state surveillance.

There are two forms of narration present in Aljafari’s film: the title card, which are sourced from the diary Aljafari kept as he rewatched his father’s surveillance tapes and which function similarly to title cards used in silent film, and the voice of his niece. While the title cards are often anecdotal or reflective, the narrative voice of the child is immediate, as if Aljafari’s niece is responding to the things she sees for the first time. When she sees her grandfather, Abdeljalil, get out of his car she exclaims, “هاي سيدو عبد! الله يرحمو” subtitled as “my grandfather abed! god bless him,” a tender and emotional comment that immediately humanizes what takes place in the grainy footage.

The ongoing occupation and its ripple effects are experienced as apparition. Police lights flash; a military vehicle whizzes by; the Aljafari’s family’s neighborhood is referred to as “the Ghetto”; a man passing by drinking a soda—the title card relaying that he has been imprisoned many times; the shadow cast by the second floor of the house, which remains unfinished since and due to the Nakba,3 is like a ghost; a burning dumpster; the mention of shootings in the area. They fade away as the attention of the viewer is drawn again to the mundane, to life.

Though the passage of time is measured by the camera’s timestamp on the lower left side of the frame, time does not function linearly. It passes in shadows, as cars move backwards, and as the day can suddenly shift to night. Often, the timestamp is erased or cropped out of the frame. Aljafari intentionally rearranges time to emphasize life. In a letter describing his approach, he writes, “the single angle somehow eliminated time as we know it in cinema, this wasn’t made for a film, it was made for life. Everything and every time existed.”4

The transformation of the footage from linear, silent, and stationary to choreographed and anecdotal “iterative and accumulating one movement sequences,”5 creates a relational space, rather than a surveilled one, in which the lived experiences of the minor figures6 from Al Ramle are perceived as novel, as significant, as historically situated7 and timeless. Nothing happens, and everything happens.

One can draw connections between Aljafari’s film and Only The Beloved Keeps Our Secrets8 by Ruanne Abou-Rahme and Basel Abbas, a video piece structured around footage taken from an Israeli military surveillance camera in 2014. The grainy footage depicts Israeli forces ambushing a group of three boys and shooting dead Yusuf Shawamreh, a fourteen year-old boy who crossed a “separation fence” near Al Khalil (Hebron) to forage for aqoub. However cruel and irrational the murder of Yusuf may be, the hyper-surveillance and criminalization of the Palestinian body is an ongoing aspect of the settler-colonial project. Earlier this month, five Palestinian children who ranged in age from eight to twelve were harassed by Israeli settlers before the military was called to arrest them for picking the same wild plant near an illegal settlement. The eldest boys of the group will face charges.9 These tactics make the body hyper-visible in order to erase it, in death and in narrative, establishing the settler colonial imaginary and perceptions as hegemonic truths, as positive––so that all other lived experiences happen in the negative.

In the work of Abou-Rahme and Abbas, the surveillance image is not static; the camera jerks back and forth, tracking the three boys as faceless black figures walking and bending down in grey and white fields. The camera jolts as the soldiers, seen as large armed black figures, ambush the boys; an armored car speeds to the area; the dying boy’s body is put in the vehicle by the soldiers. The footage, which was only released after a court injunction, is layered with text and moving images, both found and recorded, from Palestine. We see videos of protests, dances, folk songs, home demolition, people foraging, landscapes, wild plants, and abandoned developments—creating a sense of density and fragmentation. The text and images redact each other while interacting with one another, while the sound pulses through two speakers and a subwoofer.10 The accumulation and relation of these elements are felt, bodily, and they manifest an affective space between appearance and disappearance in which “uncounted bodies counter their own erasures, appearing on a street, on a link, on a feed. Words from their songs are broken up and reformed.”11 In this case, the minor figures, whose lived experiences are perceived by the settler colonial imaginary as background noise, treated as a threat or as a ghost, appear anew in mutation.

Aljafari is intimately familiar with the paradoxical position of the Palestinian body. In a master class at Festival Ciné-Palestine, Aljafari spoke about the making of his film Recollection in which he altered over fifty Israeli films shot in Jaffa from the ’60s to the ’80s to erase all traces of foregrounded Israeli characters or sets. Only the structures and figures originally mediated as background, the Palestinian residents of Jaffa, many of whom the filmmaker knows personally, are left as main characters. “In Jaffa and also in Jerusalem, [as a Palestinian] you know, you’re an outsider, you’re an outcast. You’re a ghost in your own country. That’s why I identify myself with the characters, with people I find in the background. I am one of them, in fact, and I grew up as one of them.”12 It is because Aljafari is familiar with this paradox, to be hyper-surveilled yet meant to be invisible, that he is effectively able to expose it, intuit its subversion, and negotiate the boundaries of visibility and invisibility.

The effects of such a paradox are embodied in An Unusual Summer, as people are often seen experiencing paranoia. Aljafari’s neighbor Yousef, for example, is constantly looking over his shoulder. The title cards say that he mutters to himself, “They have taken everything,” over and over. The paradox is especially intimated the short anecdote which roll before the credits: Aljafari’s father is arrested on his wedding night because the band played a song for Palestine; Aljafari himself must perform a logistical gymnastics every time he wants to drive from his neighborhood to the airport, or vice versa, so that he is not racialized by Israeli taxi drivers, and his family is not stopped for hours at a checkpoint. This is the experience of being seen as a threat, or not at all.

Near the end of the film, a title card reads, “Life must be disrupted in order to be revealed.” This is the intuitive force that drives An Unusual Summer, to reveal life. Aljafari’s film also reveals something else: in recording oneself within a surveillance state that is determined to erase you, in altering such a recording to emphasize affect and the significance of minor moments, the recording becomes a record.

1 André Elias Mazawi, “Vancouver, BC, Wednesday, April 15, 2020, 7:51PM & January 28, 2021, 8:45AM,” Received by Kamal Aljafari, Kamal Aljafari Research & Letters, 15 Apr. 2020, kamalaljafari.art/Research-Letters.

2 Kamal Aljafari, “An Unusual Summer,” Received by Ra’anan Alexandrowicz, Film Text: An Unusual Summer Film Text: An Unusual Summer, Woche Der Kritik, 24 Feb. 2021, wochederkritik.de/de_DE/magazine/film-text-an-unusual-summer-alexandrowicz-aljafari/.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 André Elias Mazawi, “Vancouver, BC, Wednesday, April 15, 2020, 7:51PM & January 28, 2021, 8:45AM,” Received by Kamal Aljafari, Kamal Aljafari Research & Letters, 15 Apr. 2020, kamalaljafari.art/Research-Letters.

6 When thinking through Palestinian conditions of erasure, historiography, and mundanity, I am always in conversation with Saidiya Hartman’s use of minor figures, which she defines as the young black women who led revolutionary lives but were considered insignificant in historical records: “They have been credited with nothing: they remain surplus women of no significance, girls deemed unfit for history and destined to be minor figures.” Saidiya Hartman, Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2020), xiv.

7 André Elias Mazawi, “Vancouver, BC, Wednesday, April 15, 2020, 7:51PM & January 28, 2021, 8:45AM,” Received by Kamal Aljafari, Kamal Aljafari Research & Letters, 15 Apr. 2020, kamalaljafari.art/Research-Letters.

8 An excerpt of the video piece is available here. Ruanne Abou-Rahme and Basel Abbas, directors. Only The Beloved Keeps Our Secrets (Extract). Vimeo, 2016, vimeo.com/161970557.

9 Al Jazeera “Video Shows Israeli Troops Detaining Palestinian Children,” Occupied West Bank News | Al Jazeera, Al Jazeera, 11 Mar. 2021, www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/3/11/video-shows-israeli-troops-detaining-palestinian-children.

10 Ruanne Abou-Rahme and Basel Abbas, “Only The Beloved Keeps Our Secrets,” Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme, 2016, baselandruanne.com/Only-The-Beloved-Keeps-Our-Secrets.

11 Ibid.

12 Kamal Aljafari, “Masterclass Kamal Aljafari: (Re)Collection: Shifting Borders between Visibility and Invisibility.” Festival Ciné-Palestine. Festival Ciné-Palestine, 27 May 2018, Paris, www.youtube.com/watch?v=wiXqn4kqBOg.

Lamia Abukhadra is an artist and writer based in Minneapolis and Beirut. Her practice studies and confronts the irrational truths present within settler colonial power structures, derived from imaginaries, ethoses, and ontological tools, and their extractive repercussions. Using Palestine as a microcosm of urgency and resistance, she embeds speculative frameworks, intuited from practices present long before the settler colonial project. Her works bring to light intimate and historical connections, poetic occurrences, and generative possibilities of survival, mutation, and self-determination.

Lamia graduated from the University of Minnesota with a BFA in interdisciplinary studio art in 2018 and is a 2019–2020 Home Workspace Program Fellow at Ashkal Alwan in Beirut. Her work has been exhibited at Waiting Room, the Quarter Gallery, Soo Visual Arts Center, Yeah Maybe, and the Katherine E. Nash Gallery in Minneapolis and in Chicago at Unpacked Mobile Gallery. Her writing has been self-published and featured in Jadaliyya and MnArtists. Lamia is a 2018–2019 Jerome Emerging Printmaking Resident at Highpoint Center for Printmaking, a 2019 resident at ACRE and the University of Michigan’s Daring Dances initiative, and a recipient of a 2017 Soap Factory Rethinking Public Spaces grant. This fall, she will be a 2021–22 Jan Van Eyck Academie Resident in Maastricht, Netherlands.

Lamia is the Communications Coordinator at Mizna.