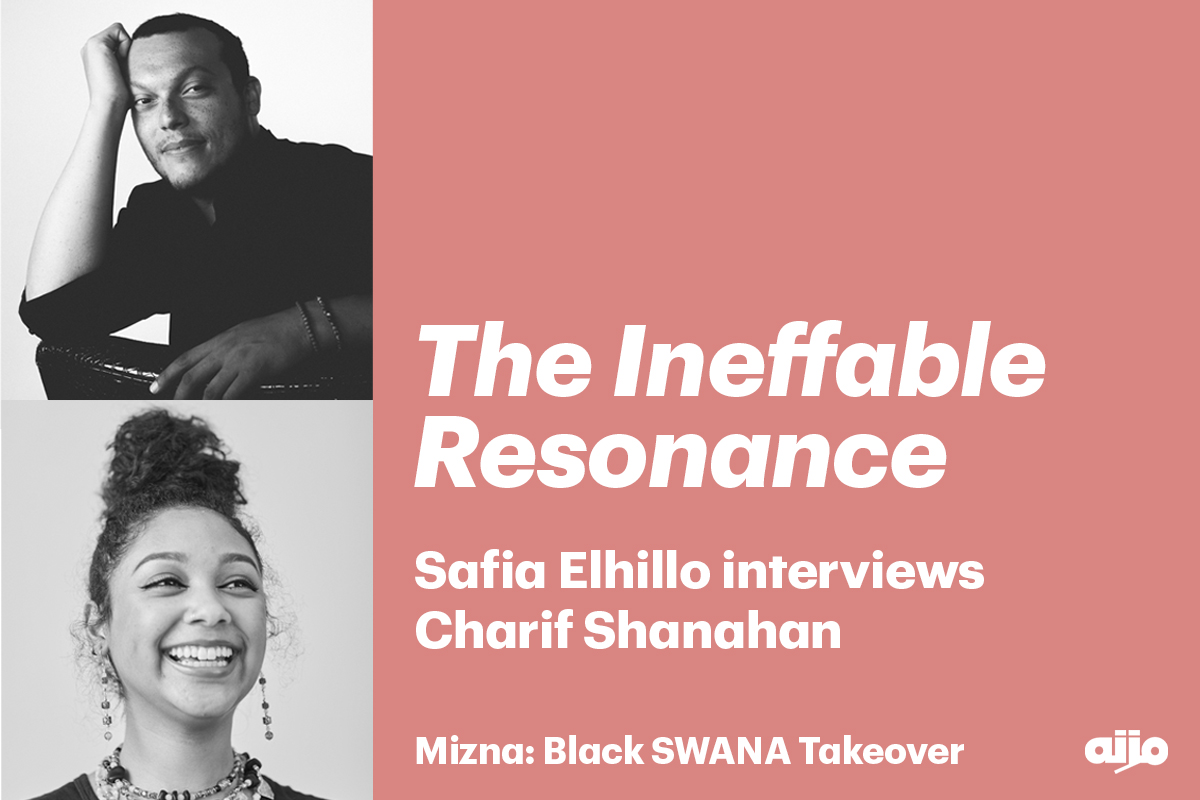

The Ineffable Resonance– Safia Elhillo interviews Charif Shanahan

This text is published as part of Mizna: 23.2: Black SWANA Takeover. Available to order here.

Poets Safia Elhillo and Charif Shanahan first met during Cave Canem’s 2014 writing retreat, and, at the end of their time together, Safia’s graduation speech was abundant with praise for Charif’s work and his depiction of the mother figure– a woman she felt she could become. Since then, both have published poetry collections, pulling inspiration from facets of their identities even as they grapple with them personally. During Safia’s book ftour for her latest collection, Girls That Never Die (Penguin Random House), and while Charif was preparing for the release of his forthcoming book, Trace Evidence (Tin House), they sat down to chat about their journey as Black artists from the Arabic-speaking world and how they find context in each other’s words. Selected poems from Trace Evidence appear after this interview.

SAFIA ELHILLO

You were one of the first English-language poets I met who was thinking about Blackness in and of the Arabic-speaking world and whose intersections came close to my own. I’d love to start by hearing you talk through how you started thinking about Blackness in your poems and how you came to a vocabulary around it.

CHARIF SHANAHAN

I think I’m still developing a vocabulary. It’s a topic that’s so undertreated and underdiscussed. When we speak from a particular vantage point, culturally, nationally, religiously, racially, using the language conferred by the context of those positions, we speak from our individual subjectivities in a way that can often flatten the complexity of the question of race on a global scale and over time, right? And so, if we’re describing Blackness, or a Black experience, using language that emerges historically from a US-American context, it’s kind of anachronistic when we’re talking about contemporary depictions and experiences of Blackness. And the language fails differently, if we’re talking across national or culture boundaries, too. So, the language pieces are really complicated and probably require a reimagining on the part not only of Black folk from the Arabic-speaking world, or Black folk, period, but of all people who are awake and alive [laughs] in the mind, and spirit.

That’s the second piece. The first piece was that I wasn’t writing about race, or really identity in any way, for a long time. I hadn’t really begun a journey of racial reckoning with myself, and so, by extension, the poems could never contain it. I mean, poems have to be always an extension of us, regardless of whether or not we’re writing about our own lives. If we write about anything, and perhaps especially when we try to write away from ourselves, like when we deliberately choose a subject that cannot be misread as autobiographical, then we are, perhaps, most stitching into that poem ourselves, our own minds, our own psychologies, predilections, predispositions.

But as a subject, race and identity, and questions around race, weren’t really in the poems. Not until I began an individual journey of healing and really began to look at what I had inherited culturally, growing up in a mixed-race, binational, bicultural, bi-religious family. When I really began to reckon with the implications of that heritage — which is gorgeous and for which I am so grateful, but which brought with it difficult questions — something in me broke open, and the poems just started to pour out of me.

SE

I remember the first poem of yours I ever got to read, “Clean Slate.” I’d love to know where in your timeline of thinking about Blackness did you write it? The speaker in that poem says, “I am be- ginning to understand that I am African.” The word beginning feels particularly striking now, when I look at your newer work and how the volume of the conversation feels like it’s been turned up louder. So was it, as the poem says, the beginning? Or had you written about it or talked about it before it entered the poems? And where do you locate your newer work in relation to “Clean Slate”?

CS

I wrote that poem probably that first summer that I went to Cave Canem’s writing retreat. Yes, it was the beginning, in a way: I’d grappled with racial questions earlier in life, but their apparent unanswerability led to my suppres- sion of them. So, it was a beginning that was also a return, we could say. The “beginning to understand” holds that sense, but the more operative component, for me, was the “African” as opposed to “Black.” It was important for me to establish my consciousness around the questions of identity that I inherited from my mother: it wasn’t just that “Blackness does not equal African. African does not equal Black,” which feels like an obvious thing to say, though is something that many seem to need to be reminded of, including some Africans themselves, but also that the North of Africa is Africa, which also feels like an obvious thing to say, though, too, can bear being repeated or affirmed. Relatedly, one of the things that I’ve had to think about a lot, too, is how to reconcile, or hold, the non-American origin of my Blackness with my Americanness.

SE

If that Cave Canem sequence of poems was the beginning, where do you locate the new poems in Trace Evidence in relation to that? Is it a completely different thing?

CS

It isn’t completely different. I remember somebody told me when I was beginning to talk about the complexities of my particular Black experience, as a kind of critique, “I mean, I understand where you’ve arrived, but you could have just been Black. You could have just written a book that put you forward as Black and affirmed that identity as given, so people would question or challenge your belonging less,” rather than the book I wrote, which demon- strates the way in which an identity that most people presume is hard, fast, fixed, given, immutable, unchallengeable, had been almost none of those things for me. That story is actually the truth, or my truth, rather than a posturing at something.

The first section of Trace Evidence is the one that feels most explicitly connect- ed to the poems in the first book. What I try to do is integrate the poems about race from a Black Arab context as a mixed-race person who is also phenotypically lighter; and demonstrate how there is always already a conversation between two threads: the complicated inheritance and interpersonal intimacy, affection, love, relationships. The third section of the book looks at time and mortality and the present moment and my relationship to the future or to projections of an arc of a life.

SE

In the time between your first book and Trace Evidence, you traveled to Morocco. how did your time there enter or shape those new poems?

CS

It was revelatory and predictable; hard and easy. I was returning to my ancestral homeland. It had been a while since I’d been there, so there was a freshness to the experience, even as there was a level of familiarity. And what I found there was what I had imagined I would find there, what I had found in my apartment in the Bronx my entire childhood — a cultivated anti-Blackness that was so integrated psychologically that even firmly Black-presenting Moroccans were aghast at the notion of even conversing about Blackness. It was hard for me during that trip, and in my life, to find Moroccans who own Morocco as a nation in Africa. So, I found, in a way, what I expected to find — and it was that that was revelatory: that I did know the narrative, that it was widespread.

Of course, there was also the accident, the bus accident, that prematurely ended my time there. The centerpiece of the collection is a long poem, “On the Overnight from Agadir,” that chronicles that experience.

SE

You are a born-and-raised New Yorker, but you have spent time in several other countries. How did you experience your body, your Blackness, your many, many intersections across these different settings? Did anything happen to the language, the vocabulary? Does that do something inside the poems?

CS

The way that my family holds race is kind of necessarily global, or at least continental. And I know that we can say all Black people in the United States carry that too. But I mean the acculturation of being born out of a different kind of cultural context within Blackness. There were ways that I had to be thinking globally to make sense of my family story, to consider blended families like ours and how we were distinct. What, at first, seemed like a denial of Blackness in my mother, I came to understand was much more complicated: when she came to the US, the identity categories germane to her experience, like woman, Arab, Muslim, Moroccan, (eventually) mother, shifted. There were more central or pressing identity categories that she had to reckon with, namely race and being read as African American, and her resistance was not necessarily to embracing the truth of our Black heritage, it was to the very real sense that, by doing so, her identities, as she understood them, were being taken away from her.

The reverse happened to me when I left the US, whereby it was the same process — the operative identity categories shifted, in a way. When I first got to Europe, I was in London for two years. I was working in the corporate world, trying to figure out how to be a poet while working at Bloomberg LP, writing poems and reading Neruda on my lunch break. People in suits were like, “What’s with that guy with the Neruda?” [laughs] I was totally a fish out of water, although I did well there. As far as identity was concerned, I was the American guy, the guy from New York, the gay guy, maybe, oh, you know, the bloke with the Irish father and Moroccan mum. But when the cultural heritage, the nations from which my parents emerge were named, it was never through a racial lens. So, it wasn’t like the mixed-race guy, which was interesting and kind of a relief, to be honest.

Then I moved to Istanbul and Barcelona and then eventually Zurich, where I lived with my ex-partner who is Swiss. And there’s a poem in Trace Evidence called “RACE” about those years and the love of my ex-partner and how that kind of anchored me during that time. I think there was something deep, deep inside me that was looking for a context, or looking to experiment within a context, where my difference made sense or had an easy explanation, a tangible and easy thing to point to, to identify. There, I was different because not European-born; done! Whereas my difference always felt much more complicated and fraught and painful in the United States.

Morocco is the only place that I’ve been where my freckles sometimes throw people off, but I mostly just look like everybody else. Because there are so many different presentations. Many Moroccans probably have a similar kind of ethnic composition as me, even with my white American father and Arab mother.

SE

We’re at the last question, and, I’m wondering, are there partic- ular writers and thinkers whose work has guided the conversa- tion happening in your own work? And are there any particular writers and thinkers whose work kept you company as you were making Trace Evidence?

CS

I love that question. Because [pauses] it articulates or it reaches for the thing that I am reaching for in the work, which is a return to or a reminder of the innate knowledge and wisdom that exists inside all of us; I want to believe that we are all the same thing, that we are one, in a way that I think would make people roll their eyes, because we live in such a divided and divisive world. And I don’t mean to say that our differences don’t exist, because our differences are beautiful, and many, and super powerful. It’s kind of like that initial state of being, before language, before we are named, and gendered, and raced, and languaged, and cultured. That state must exist, because we don’t come into the world with those things, right? That moment of connection, of return to our oneness, is something that I think happens in profound experiences of art.

When we sit down and read a poem, what I believe is happening is that there’s this alchemical process between the words on the page — the imagination and the craft of the writer — and the subjectivity, the imagination, the personal history of the individual reader. And then the poem drops us back out into the world or into our own experience, and that ineffable resonance, like the afterlife or the echo of a poem that we feel in our body, that we recognize when something deep inside us has been touched, that resonance, I believe, our being in that connected state from which we then slowly return to our own subjectivities — to our own self, as it were.

And so the question that you asked, about who I was reading, who sustained me? I would name you as one poet. I have been able in my life to find so few people, much less English-language poets, who are writing out of the kind of intersectionality that we share of an Arabic-speaking and Black world, right? And so it was important to me to find you at Cave Canem and to know that I wasn’t alone in this experience.

I also thought of Toni Morrison and that famous quote of hers that’s some- thing like, “If there is a book that you want to read, and no one’s written it, you have to be the one to write it.” I don’t claim to have done that yet, but I certainly am trying to put poems into the world that capture an experience that was so complicated and hard, precisely because I couldn’t find it anywhere around me.

Filmmakers and artists, Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige question the fabrication of images and representations, the construction of imaginaries, and the writing of history. Their works create thematic and formal links between photography, video, performance, installation, sculpture, and cinema, being documentary or fiction film. Together, they have directed numerous films that have been shown and awarded in the most important international film festivals before having theatrical releases in many countries. The artists are known for their longterm research which is based on personal or political documents, with particular interests in the traces of the invisible and the absent, histories kept secret such as the disappearances during the Lebanese Civil War, a forgotten space project from the 1960s, the strange consequences of internet scams and spams, or the geological and archaeological undergrounds of cities.

Marie-Nour Hechaime has worked as a curator at the Sursock Museum in Beirut since 2020. She is interested and invested in projects and productions at the intersection of arts, activism, and societal issues that strive to articulate and exercise points of interrelation between disciplines, as well as alternative modes of generating knowledge and collaboration.