September 21, 2022

Looking Through the Eternal Present —Marie-Nour Hechaime interviews Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige

This text is published as part of Mizna: 23.1: Tribute to Etel Adnan. Available to order here.

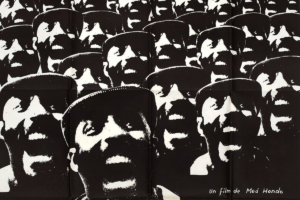

Ismyrna begins with the recollection of the dreadful night of 1922 when Joana Hadjithomas’s grandfather had to flee — alongside his family — from Smyrna in flames. The fifty-minute film by artist duo Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige, produced in conversation with artist and poet Etel Adnan, explores what happens to fading cities whose memories are born from the violent dispossessions and ruptures that trans- form them into myth. Toward the end of the film, Joana Hadjithomas reflects on the stories relayed to her that have become part of her “imaginary” — stories of which she is “no longer sure where they begin and where [her] imagination ends them.” Acknowledging the loss and grief absorbed through the transmission of these memories, Etel Adnan highlights that Smyrna is no longer here but rather remains “in you.”

MARIE-NOUR HECHAIME

How did you meet Etel Adnan and what pushed you to make Ismyrna years later?

JOANA HADJITHOMAS

Khalil met her and Simone [Fattal] in San Francisco in ’99 and I met them in Beirut in 2001. Immediately, we decided to go to Izmir together. One of the first things that linked us and shaped our friendship was the idea of Izmir, also Smyrna or Ismyrna, as our families would refer to the city. My grandfather was born there and had to leave at the age of twelve in 1922. He was Greek, as was Etel’s mother who had to leave two or three years later with Etel’s father, who was Syrian but part of the Ottoman Army.

KHALIL JOREIGE

Joana’s family name intrigued Etel, and sparked the conversation.

JH

She had never been to Izmir and no one from my family had ever set foot there, despite talking about it all the time. For years, Etel and I shared a dream of traveling together to Izmir and making a film on the journey. We had never been there and our families had never returned. But Etel was unable to travel by plane anymore. We considered going to Venice by train, then taking a two-week boat journey to Izmir. The plan seemed too complicated, and instead we talked, staying in the place where we were, we talked about elsewhere, about that elsewhere.

KJ

The material of the film is not three interviews. It’s a conversation across several years.

MNH

And then you edited a lot, I presume.

JH

We would talk about anything and everything, with a lot of digressions. We recorded hours of conversations. Of course there was a lot of editing. But we wanted to keep the feeling of fluidity to preserve the long conversation that we have had together and share this moment of intimacy.

KJ

A conversation is something that starts at one point and takes you to another direction. You start somewhere but you don’t know where it will take you. Each time, we discovered new places, new territories, new issues, new destinations.

JH

One of our main interests was to talk about transmission and the way these personal stories were transmitted to us with the gap of generations. But also to talk about the Ottoman Empire and the consequences of its presence and disappearance.

MNH

I remember watching your film Around the Pink House (1999) in my early twenties and being struck by the shot depicting destruction and reconstruction taking place. You can see downtown Beirut being reconfigure, allowing for the mystification of prewar Beirut–”the golden Beirut.” How do you think these two myths, of Beirut and Izmir, differ in their transmissions?

JH

It’s very different, because we were born in Beirut, we live and work there. In Ismyrna, there is an imaginary — without images. It’s an oral transmission of all those stories. We did not inherit images of Smyrna, only narratives. I had built myself an imaginary place through stories, transmitted by my grandfa- ther who, lying in his bed, used to replay scenes incessantly to us. An audience captivated in spite of endless repetitions. It’s a place you don’t know. You don’t really understand. And so it’s more about deconstructing this nostalgia. This Izmir, or Smyrna, was a lost paradise for Etel’s mother and for my grandfather, a city that has changed a lot. You live with those fantasies, those regrets, the trau- ma of others. It is something that you hold within you. It nourishes you, without feeling it. But for Beirut, it was totally different. The idea and mystified presen- tations of Beirut before the war, in the ’60s, is something that we had to confront and deconstruct. We went against a dangerous nostalgia that is always politically conservative.

KJ

On the one hand, I am a witness and an actor of what’s happening. On the other hand, I am structured by a history that came from another. I am the witness of the witness. It’s not exactly the same relation. When we started to produce our own images, we had to create our own representations and our own possible narratives. To make images that resemble us, to reconsider our relationship to the world and the country at that time. Build our own imaginary.

JH

But it’s also cities — Izmir, Beirut, Alexandria — that were able to be what is seen as cosmopolitan, that had many possibilities, many languages, many cultures, many identities, that would live together . . . Places maybe less hegemonic, places where you are torn by many temporalities, by many movements, places of fragility.

KJ

There is a risk to consider that these places are a kind of allegory that is not related to anything anymore, and this is something we always try to avoid, the risk of dwelling in a mythical world. Those imaginaries are related to con- temporary worlds and to the notion of territory: to the word cosmopolitan (loaded by too many things), we prefer instead to use the notion of being contemporaneous, as sharing the same time. Here, we are trying to shift the conception of a territory from a geography to a temporality—temporality being something shared, sharing the same issue or concern.

JH

At the center of our conversation with Etel, there is this idea of the contemporaneous rather than notions of nationalism. For example, Etel and I never talked about the fact that her father was part of the Ottoman army, while my grandfather was Greek and persecuted by that army.

KJ

They discovered this ten years later. They were talking a lot about this shared history and it took them years to realize.

JH

It was never an issue. In a way, we decided to rebuild things differently. Each one of us had a link to the city, the links intertwined, mingled as we rebuilt a shared, although opposed, past. While enemies, Etel’s father and my grandfather came from two lost, defeated worlds, and Etel and I internalized that loss, it shaped us and brought us closer to one another . . . It is beyond history, or perhaps it is history itself. A territory of art, that additional continent to borrow from Godard, in reference to art and film, is what we chose to share together. Even after all that appeared evidently and clearly in the film, this connec tion we shared for seventeen years was stronger than reality, and did not manage to overcome it.

KJ

It is a shared heritage that was more important: not only the idea of the lost paradise but also the idea of the region at that moment, how it evolved, and how, of course, the civil war in Lebanon was a consequence of all this evolution. We were also talking about a certain idea of living together that had disappeared. So yes, it’s a very different kind of deconstruction. One of them, we never expe- rienced, we never lived, and politically, it’s part of the past, whereas when we were living in Lebanon after the civil war and producing our works, we had this feeling and this faith that what we were doing would contribute to a conversation around images and representation. And of course, politics.

JH

We felt that it’s part of what we are building as an imaginary. It’s very important to recuperate our images, to recuperate something that is closer to us as a shared history, in a country where there is no writing of history that can be shared.

KJ

We should also define how we conceive the word imaginary, because we are using it a lot. It’s fact and fiction that are not equal or same, but they are, together, constituting a framework of representing ourselves. It comes from the French “imaginaire,” but in English its translation does not exist.

MNH

Yes, you use the term imaginary a lot, even in the film. At one point, you mention how you don’t know anymore where the stories begin and where your imagination ends them and how they become almost a concrete memory–which I think is what happens with all family histories. I found that, to use a term you don’t like–kind of universal.

JH

I understand why you’re saying this. We often work not only from Lebanon or Beirut, but also from our house. It is when you are very specific that you can be open. I’m not against this idea of being universal when you use it as capable of being understood and felt by many. I think that when we try to be very specific, it’s to try to have conversations with a lot of people. When we make art, the most important thing for us is not only to express what we feel but also to open conversations, to share questions, anxieties.

KJ

We say that Ismyrna is a film about Joana’s family and Etel’s family. But it has echoes also for my family, especially the Palestinian side. It has echoes for a lot of people, because it’s a film about transmission. And transmission was always at the core of our interests. But it is also a kind of mystery. How come, by being so specific, so accurate and precise, you can echo a larger scale?

JH

I think what makes the film very close to the viewer is the fact that Etel talks in a very simple yet profound and deep way at the same time. While she’s talking, a lot of images, poetic images, come up, and so you understand immediately.

MNH

Etel’s poetry, as well, holds this kind of power. Can you tell me more about your relationship with poetry within your work and within your larger project I Stared at Beauty So Much?

JH

I Stared at Beauty So Much is a line from one of Cavafy’s poems that became the title of a project started in 2013. Firstly, we worked on the Greek poet Constantine Cavafy. We didn’t really know a lot about him. But when we started reading his poem titled “Waiting for the Barbarians,” we felt we needed to put it into images and use poetry to counter the feeling of chaos that was prevailing at that time, and still is. In 2013, everyone was talking about Islamism and Barbar- ians and so we felt this was an incredible poem to talk about the relations we have to others. At the same time, we also wanted to work on the idea of art and poetry as a territory more than a national or geographic one. Cavafy was a Hel- lenic poet, writing in Greek, but who lived all his life in Egypt. Etel wrote in French and English, but she was, nevertheless, an Arab poet.

KJ

These writers are all building extensions of a world where you can live, cre- ating the possibility of addressing the other, creating links be it to Jenin or even to the moon. There’s an extension of the field of struggle [domaine de la lutte, in French] touching on a whole constellation of things. We like to work with others, to collaborate, or to borrow the eyes, the words of others, the knowledge, whether it is from archaeologists, journalists, or geologists, or poets.

MNH

In one of your installations called Zig Zag Over Time (2017), you make an argument against a strictly linear, horizontal account of history. And in Ismyrna, there is a moment when Etel is reading from her leporello titled “Family Histories and the End of the Ottoman Empire.” It’s an account of dismantling of the Ottoman Empire where she makes numerous transgressions, flashbacks, and includes personal stories and larger political ones. It’s quite similar to the way you intertwine multiple narrations. Could you expand on this way of writing history?

JH

Earlier you quoted a sentence in the film where I say that in a way, I’m no longer sure where these stories begin in reality and where my imagination ends them, how they start and how I finish them. Maybe it’s not very important, because it’s my personal experience of history. This is also what Etel is saying in the leporello when she’s talking about her personal relation to history, her personal relation to her father. It is part of a more personal story for each one of us and is linked to our family. It constitutes us, and it’s not done in a very linear, logical, or chronological way. It’s memories that are recalled, without under- standing what is right, wrong, true, or false. But when you write history, it’s totally different. We are not historians. We are two persons telling their stories, and in a way recalling a collective history by doing so. For historians — unlike artists — chronology is important.

KJ

Archeologists taught us that history sometimes is seen more as actions and not as chronological layers. It’s not linear. It is not layers that are very prop- erly structured. All is upside down, palimpsests. We live in a part of the world, and specifically in Lebanon, where we are always confronted with ruptures in our history. These ruptures create discontinuities, temporal ruptures, gaps in time. These unconformities have consequences for the way that we are dealing with our history, which cannot be linear. This is at the core of the way that Etel considers history or deals with it. If you noticed, and especially when she’s writing a leporello, it is not drafted before and it is produced in one go. It is like a breathing.

JH

Archaeology and geology have taught us that a lot of things are cyclical. It is important for us to see those discontinuities in history and to be able to accept them, and hope for continuity back. Or if not continuity, maybe regeneration. These discontinuities are very important when we are telling our own personal stories. And this is why you have this feeling, also, in the film, of going back and forth, those zig-zags that we do.

KJ

Rhizomatic relation.

JH

The film is also about accepting that our personal stories and memories take us places. When I go to Izmir with Khalil, we start walking without really knowing where to go, without knowing which images are important to bring back. Nothing can fill what we created when we listened to the stories of our families over and over again. When I came back from Izmir, I had this feeling that I left the trauma inherited by those family stories there, that it went out in a great rush which I describe in the film. Something about all the memories and trauma of the other that I was holding and that were inhabiting me, in a way, I left them there. When Etel leaves her suitcase at her friend’s, in a way she’s free- ing herself. There’s a lot of sorrow to lose all this. But at the same time, you get out of the nostalgia, the nostalgia of others. And it is very liberating. And it is very important for Khalil and Etel and me to get out of the nostalgia, and to live what Etel would call an eternal present. She was like that. She would acknowl- edge the past, it was very important for her. But at the same time, she would live totally in the present which is our case as well.

MNH

The most emotional moment of the film for me is when she recalls leaving her suitcase and the fact that she realized her friend, who was from an Armenian family, would open the suitcase and would see the photo of her father in the Ottoman Army but also the pictures of him with Atatürk. She is able to relay terrible things that took place in the Ottoman Empire, not just in Izmir, but also the Armenian genocide, but to do so without emitting a judgement on her father.

JH

This is what we mean when we were saying that Etel’s father and my grandfather were not part of the same side which was not a problem for us as we are part of another moment of history. We can make our own choices. When Etel talks about this suitcase, it’s heartbreaking, because in a way, she’s so free of her choices, she didn’t realize the consequences of what was contained in the suit- case. But it has the strength and the beauty of someone who was free. Free to make decisions about her life without the weight of nationalism and identity. She freed herself from that. At a time when those are very important and always brought back, I think we should remember this. Do we rewrite our history, when we lay down the suitcases transmitted by our parents?

KJ

What stories constitute us, and how can we emancipate ourselves from their grip? Neither of us placed our sense of belonging as a standard bearer. It enabled us to talk about the Ottoman Empire and revisit the paradoxical aspect of the great changes the region went through after its collapse. The porous borders, the constant movement, the rise of nationalism, independence, after a 400-year-long history of colonization, but also the resultant loss of a form of living together.

MNH

A lot of your work is about these latent and dormant histories to which you try to give physicality. I feel that when you go back to Izmir, it isn’t just about seeing, but also walking there

JH

It was a fear of being confronted with a mythical Izmir. Etel traveled all over the world but never went there.

KJ

Etel was wondering, “Why didn’t I go there?” So, we are trying, also, in the film, to understand that maybe those images were part of something. I think those latent images that you are talking about were not revealed when we- went to Izmir. Something else happened.

JH

Some things stay with us. Etel kept those latent images. It was an imaginary that stayed latent, just like I will keep the stories of my grandfather without confronting them with the reality of what Izmir is today, because Smyrna has disappeared, and his house, and all his belongings. All the places where he went were burned.

KJ

Actually, there is an attempt, which Joana referred to in the film — it’s what her grandfather tried to do with the safe that he is reconstituting exactly like it was. We are exactly in a different position. We’re not trying to see Smyrna in Izmir. We are just acknowledging that time passed and accept being confronted with a new place with its beauty. When Etel is looking at the pictures, we are discovering this geography. And the mountains. The mountains were quite bizarre for us, because they looked like her paintings.

JH

Yeah. This is maybe something about latent things that infuse in you. But maybe we can make a distinction between reconstitution and reactivation. It’s something that we worked on a lot, for example, when we did The Lebanese Rocket Society, the film and the artworks. We worked on the ’60s and the space project and it brings a lot of nostalgia back, and this “Ah, look where we were and where we are today.” Even if we really wanted to tell the story, we really didn’t want people to have the feelings that we were going there. So, we worked a lot on this idea that we don’t reconstitute, we reactivate. And I think that, if my grand- father was reconstituting, he was reconstituting something that he had lost, and he wanted it exactly the same.

KJ

But reactivating, it can be just by an invocation of the past. This goes back to a concept drawn in the preface of “The Crisis in Culture” by Hannah Ar- endt, where she’s talking about this impossibility to move, stuck in between past and future, to be in a breach. So we recognize ourselves in those breaches, mean- ing that we feel that we are in the middle of a breach where you cannot go back and you cannot continue because something is broken, because an event or an accident happened. So you have to invoke the past to be able to project yourself into another history. Be it history of art, history of a medium, or anything like that. For us, this is really central. When we were talking about the different rup- tures — this is how you deal with the ruptures. How you can continue after, in a world of discontinuity. The question of transmission is at the core of this ques- tion. There’s no recipe that you can apply each time. It will be too easy. You have to reinvent different ways to see if the tools of the past are still relevant in the present and can help you to live now.

JH

In the film, Etel answers this question. Because she says that memory is like a paper, like photography, where you imprint—

KJ

Magnetic paper.

JH

It’s magnetic paper, where you imprint, with the sun, some images. There is your personal memory that is something that can serve history, but it’s not at all the same. And this is why, for example, for Khalil and me, we never had a problem of memory, I don’t think it’s true. I think we have a lot of memories, even if they’re not well-set. But it’s something that is part of us. It’s more of a problem of sharing a history, that is something that creates, also, a lot of rupture. And even if this history has its discontinuities, like we were saying, it’s some- thing that we should try to share together. And maybe it’s one of the most prob- lematic things that we have in Lebanon, for example.

MNH

There is a video of Rabih Mroué titled Old House from 2006. It is footage of a house falling and standing up again through playback as well as text about remembering and forgetting, and it’s a repetition. It’s kind of poetic. It’s about the importance of both remembering and forgetting–together–in order not to repeat when there’s this willingness to erase.

JH

Without living in the past, it is important to be able to make the past part of your life. We had this impression that the past was being put into brackets, especially at the end of the civil war. And for us, this idea was not acceptable. The system that came after the civil war, which was an economic and liberal system based on amnesic reconstruction, led us to where we are today. How did we pass from one moment to another? There’s no transition. What is going to happen? This anxiety fed a lot of what we are doing.

MNH

Talking about the current situation in Lebanon, did it feel, in some way, perhaps not déjà vu, but as if you had a premonition about this?

JH

What happened in Lebanon, I can’t say that it was a déjà vu. We would fear that something would happen. But what happened — this collapse — was so strong. We didn’t expect it to be as fast, as strong, even if we could see that something was going to happen, and feared that it would.

KJ

I will make a distinction between the situation from 2019 and the explosion of August 4, 2020, which is something that was quite different. Let’s say at the beginning, we were afraid of the collapse. We were thinking that this was not possible, and it was a dead end. But after, there is a kind of unimaginable experience, let’s call it, that is taking us to other places that are completely unknown, even in terms of representation scale.

JH

Is poetry, art, still possible? What are the forms it will take after such an event? This is what we wonder and experience these days. We recall Orpheus sadden by the loss of Eurydice and dismembered by the maenads furious of being neglected. But alone, his head, was still singing . . .

MNH

To circle back to the film, would you one day think go doing another work about this experience?

KJ

Etel gave us certain places where we have to go, to see specific things. Sto- ries, people we have to film, and meet. Transmission.

JH

We have missions.

KJ

So, we will fulfill those missions.

Filmmakers and artists, Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige question the fabrication of images and representations, the construction of imaginaries, and the writing of history. Their works create thematic and formal links between photography, video, performance, installation, sculpture, and cinema, being documentary or fiction film. Together, they have directed numerous films that have been shown and awarded in the most important international film festivals before having theatrical releases in many countries. The artists are known for their longterm research which is based on personal or political documents, with particular interests in the traces of the invisible and the absent, histories kept secret such as the disappearances during the Lebanese Civil War, a forgotten space project from the 1960s, the strange consequences of internet scams and spams, or the geological and archaeological undergrounds of cities.

Marie-Nour Hechaime has worked as a curator at the Sursock Museum in Beirut since 2020. She is interested and invested in projects and productions at the intersection of arts, activism, and societal issues that strive to articulate and exercise points of interrelation between disciplines, as well as alternative modes of generating knowledge and collaboration.