March 1, 2024

Mary of Gaza

trans. by Huda Fakhreddine

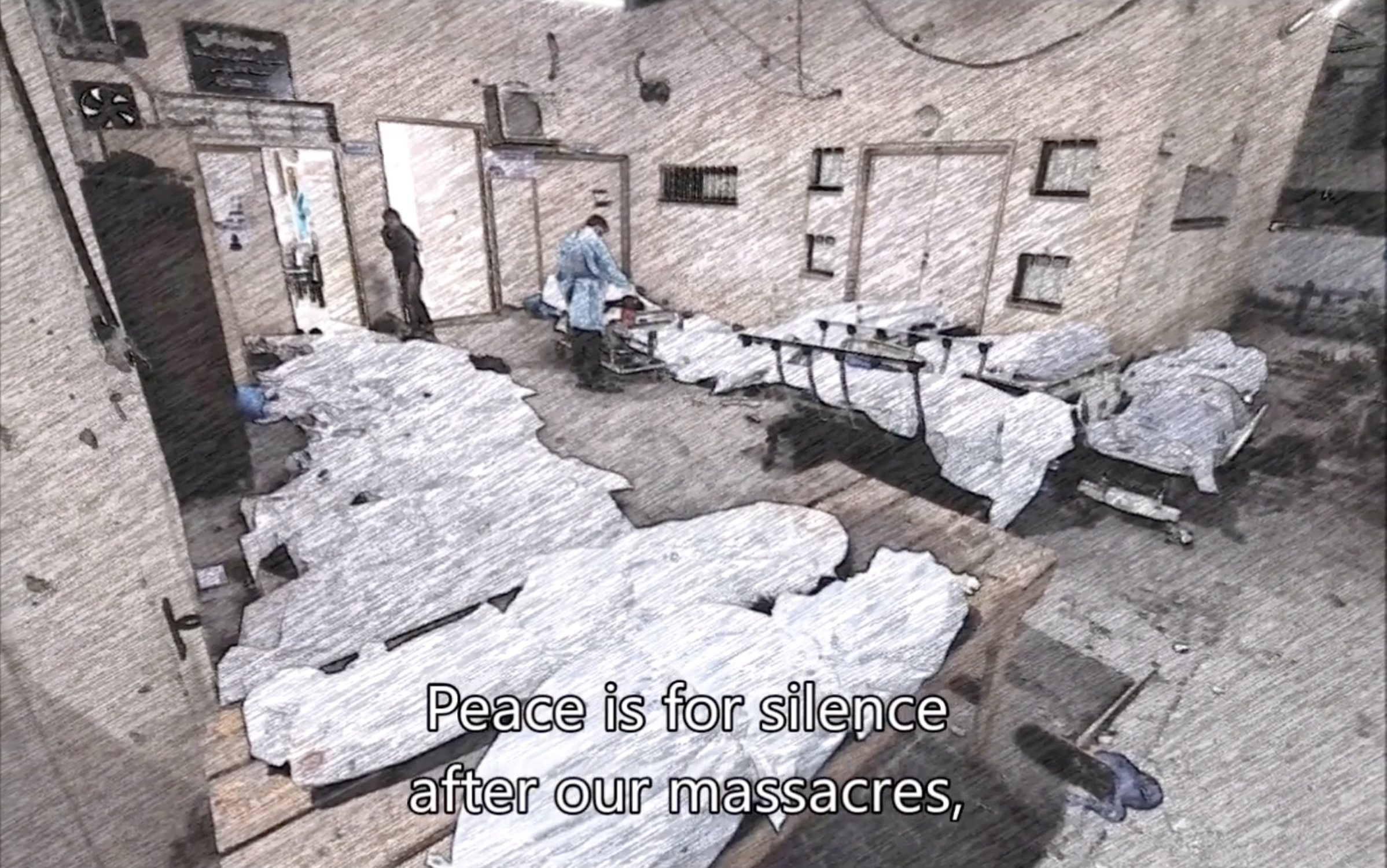

It is one of the greatest honors, bestowed to me in my brief time on earth, to publish the living legend that is Palestinian author Ibrahim Nasrallah. This piece comes to us thanks to the translation by Huda Fakhreddine, originally produced for a devastating video poem created by Nasrallah himself. Just as the poem itself is heavy with the unflinching weight of the ongoing genocide in Gaza—in both necrotic images and references to martyred poets such as Refaat Alareer— so too does the video poem force its audience to bear witness to these atrocities of settler-colonialism.

To our audiences: the images in this video poem are graphic and difficult to watch, it has been flagged by YouTube as age-restricted content. Please be aware of that before you decide to watch the video. However, we hope that these images can also function as an opportunity to ask: how can Western, especially US-based, viewers bear the responsibility of the images coming from Gaza today? To whom do we turn, in the midst of genocide, and from whom are we turning away?

—George Abraham, Mizna executive editor

Peace is for every brother who

like an enemy besieges us

and every brother who passes

over our death to build his throne

on our ruins.

—Ibrahim Nasrallah (tr. by Huda Fakhreddine)

Mary of Gaza

by Ibrahim Nasrallah

Translated from the Arabic by Huda Fakhreddine

Peace on earth is not for us,

not for my son, not for yours,

Mary said to Mary . . .

O sister of my land, sister of my footsteps on this land,

sister of my soul, my prayers,

sister of dawn in its clarity, sister of my death in its calamity,

here in what remains for us of death and what remains of life.

Peace on earth is not for us.

Does the sky above not see us or do the crosses on our backs

in the fields of bitter blood

obscure us?

Peace on earth is not for us.

It is for our enemies, O God,

for their planes. It is for death as it descends

and death as it ascends,

for death as it speaks, lies, and dances.

Nothing satisfies it,

neither our blood in sorrow, nor our blood in beauty,

neither our blood in the seas, nor our blood in the fields.

Our blood in the mountains,

our blood in the soil,

our blood in the sands,

our blood in the answer,

our blood in the question,

our blood in the north,

our blood in the south,

our blood in peace,

our blood in war . . .

None of it satisfies.

Peace is for our enemies, O God,

for their guards in distant lands

and their guards in nearby lands.

Peace is for every brother who

like an enemy besieges us

and every brother who passes

over our death to build his throne

on our ruins.

There is no place here for a butterfly in a girl who lost her feet,

no place for a lover to be killed by love, no place for planes,

no place for the poem exulting its poet who writes,

“If I must die, you must live to tell my story.”*

The sea is not for the bird or the beloved,

and the sky has turned its back on us like a foreign land.

Peace on this earth is not for us.

Peace is for others. It is for children other than mine.

Peace is for silence after our massacres,

before our massacres

amid our massacres.

Peace is for silence when we scream

and silence when we are silenced.

Peace is the voice that orders: kill them

and then kills us with silence.

Peace on earth is not for us.

It is for tyrants, cock-headed leaders,

and all the armies of dust.

It is for destruction,

for those who kill the young and old,

for soldiers and those who shackle the horizon.

It is for the ones who shed blood, hate the martyr,

and kill the witnesses.

Peace is for a tyrant here and a tyrant there,

for tails barking here and here,

and for weapons hissing everywhere.

It is for the one now gouging my eyes

so I don’t see you, O God.

Take everything, O God, and keep us here,

close to our sea and the graves of our loved ones

and our homes, here.

We will not disappear. Close we will remain.

Take us or keep us if you wish,

whenever or however you want. Close

to your heart’s eye we will remain.

Or, O God, be our fortress.

We will not escape our death, if night falls.

We will remain, O God, at the doors of your soul:

the church, the mosque, the sea,

the soil, the palm trees, and life

or what little of it survives.

Or, O God, take us but keep a little of our souls here,

some of our remains, here, on the thresholds of our homes

and their ruins. For peace on this earth

is not for us.

The peace we long for, dream of, and love

is not for us.

The peace that is as simple as my mother’s tears

in joy and sorrow

is not for us.

Peace that flies like a wing,

lands like a wing,

peace as beautiful as a song,

as gentle as laughter,

is not for us.

Not for us is a peace as tame as our cat

before they killed her.

And since she died, she still hungers,

moans, and purrs, and as we move

from a room in the north

to a tent in the south,

our cat still follows behind.

Peace on this earth is not for us,

not for Gaza when it rejoices in the spring like children,

not for Akka, awake for a thousand years,

guarding us like our grandmothers,

not for the beautiful Jaffa,

not for Jesus who rose from our blood,

then from our flesh,

then from our land and our endless resurrections.

Peace on this earth is not for us,

not for your holy Jerusalem, O God,

ascending with your Prophet and our Quran.

O God, peace on this earth will be mine, mine then yours.

Since the children of my soul ascended the sky to you,

peace has become the butterflies fluttering

between their fingers.

Nothing remains for me here but their remains,

a long day that moans, ruined thresholds, and names

covered with feathers of fallen doves.

Between their fingers the butterfly’s sun sets

and the wound of the horizon.

I said nothing to the butterfly.

I let the little wings flutter like my soul

between their fingers and travel

between ashes and dew.

I will sing in the name of twenty . . . thirty thousand,

killed and risen on this land of ours.

I will not say: peace is for those who kill, uproot, and burn.

Peace on this earth was ours before them here,

and peace on this earth will be ours after them.

Peace is ours. Peace is ours.

*A line by martyred poet Refaat Alareer

مريم غـــزة

إبراهيم نصر الله

السّلامُ على الأرضِ ليسَ لنا

ليس لابني أو ابنك

مريمُ قالت لمريمَ . . .

يا أُختَ أرضي وأختَ خطايَ على الأرضِ

يا أختَ روحي وأختَ صلاتي

وأختَ الضُّحى في الوضوحِ وأختَ مماتي العظيمِ هنا

.وما قد تبقّى لنا من مماتٍ وما قد تبقّى لنا من حياةِ

السّلامُ على الأرض ليس لنا

أهذي السماءُ التي فوقَنا

لا ترانا؟

أَمَ أنَّ الصليبَ على ظهرنا

في حقول الدَّم المرِّ يحجُبُنا

السّلام على الأرض ليس لنا؟

السّلام لأعدائِنا يا إلهيْ

وللطائراتِ، وللموتِ يهبطُ، للموت يصعدُ

للموت يحكي، ويكذبُ، يرقصُ

لا شيءَ يكفيه

لا دمُنا في الفجيعةِ

أو دمُنا في الجمالِ

ولا دمُنا في البحار ولا دمُنا في السهول ولا دمُنا في الجبالِ

ولا دمُنا في التراب ولا دمنا في الرّمالِ

ولا دمُنا في الإجابة أو دمُنا في السؤالِ

ولا دمُنا في الشمالِ ولا دمُنا في الجنوبِ

ولا دمُنا في السّلام ولا دمُنا في الحروبِ

السّلام لأعدائِنا يا إلهيْ

لحرّاسِهم في البلادِ البعيدةْ

ولحرّاسِهم في البلادِ القريبةْ

لكلِّ أخٍ كالعدوِّ أتى ليُحاصرَنا

ولكلِّ أخٍ مرّ من موتِنا ليكون له عرشُهُ في الخرائبِ ما بعدَنا

لا مكان هنا للفراشة في طفلة فقدت قدميها

ولا للحبيب ليقتلَه الحبُّ، لا الطائراتُ،

ولا للقصيدةِ تزهو بشاعرها وهو يكتب ”عشْ أنتَ حين أموتُ لتروي الحكايةَ“*

لا بحر للطير أو للحبيبةْ

والسّماء أدارتْ لنا ظهرها كالبلاد الغريبةْ

السلامُ على الأرض ليس لنا

السّلامُ لغيري وغير صغاري

وللصّمتِ بعدَ مجازِرنا

وللصّمتِ قبلَ مجازِرنا

وللصّمتِ بين مجازرِنا

وللصّمتِ إن نحنُ كنّا صرَخْنا

وللصّمتِ إن نحنُ كنّا صمَتْنا

وللصّوتِ حين يشيرُ إلينا:

اقتلوهمْ، وبالصّمتِ يَقتُلُنا

السّلام على الأرض ليس لنا

إنّه للطغاة وللرؤساءِ الديوكِ وكل الجيوش الغُبارْ

إنّه للدّمار وأشباهِ من يَقتلونَ الصّغارَ على الأرضِ . . . أو يَقتلونَ الكبارْ

إنّه للجنودِ ومن يَحشُرونَ المدى في القيودْ

ومن يَسفِكونَ الدّماءَ ومن يَكرهونَ الشَّهيدَ ومن يَقتُلونَ الشّهودْ

السّلام لطاغيةٍ ههنا . . .

والسّلام لطاغيةٍ ههناكْ

لذيول النباح هنا . . . وهنا

ولكل فحيح السلاحِ هناكْ

والسّلام لمن يفقأُ الآن عينيَّ كي لا أراكْ

إلهيَ خُذْ كلَّ شيءٍ ودَعْنا قريبينَ من بحرِنا ههنا ومقابر ِأحبابِنا ههنا ومنازِلنا

لن نغيب، سنبقى قريبينَ . . .

تأخذُنا إن أردتَ.. وتتركُنا إن أردتَ

متى شئتَ أو كيفما شئتَ

لسنا بعيدينَ عن عينِ قلبكَ

أوْ.. إلهيَ كنْ سُوْرَنا لن نفرّ َ—إذا هبطَ الليل- من موتِنا

إلهي سنبقى بأبوابِ روحكَ:

أعني الكنيسةَ، والمسجدَ، البحرَ

أعني الترابَ وأعني النخيلَ

وأعني الحياةَ إذا ظلّ فيها حياةٌ هنا

أوْ . . . إلهيَ خذْنا ودَعْ ههنا بعض أرواحِنا

قربَ ما قد تبقّى لنا من بيوتٍ ومن عتباتٍ كأشلائِنا

فالسّلام على الأرض ليس لنا

السلام الذي نشتهي، ونحبُّ، ونحلَمُ، نشتاقُ . . . ليس لنا

السلامُ البسيطُ كدمعةِ أُمّيَ في العرسِ والحزنِ ليس لنا

السّلام الذي كجناحٍ يطيرُ

السّلام الذي كجناحٍ يحطُّ

السّلام الجميلُ كأغنيةٍ

والسّلام الأليفُ كضحكِتنا

والسّلام الأليفُ كقطتِنا قبل أن يقتلوها

إلهيَ لكنها منذ ماتت تجوع تموءُ تحنُّ تهرُّ ومن غرفة في الشمال إلى خيمة في الجنوب تتابعُنا

السلام على الأرضِ ليس لنا

لا لغزةَ إن فرحتْ بالربيع كأطفالنا

أو لعكا التي سهرتْ ألفَ عام لتحرسَنا مثلَ جدَّاتنا

أو ليافا الجميلةِ

أو ليسوعَ الذي قام من دمِنا، ثم من لحمنا، ثم من أرضنا وقياماتنا

السّلام على الأرض ليس لنا أو لقُدْسكَ عاليةً بالنبيِّ وقرآننا

السلام على الأرضِ ليس لنا

السّلام على الأرض لي يا إلهيَ.. لي ثم لكْ

للفَراش الذي يتنقّل بين أصابعِ أبناء روحيَ مُذ صعدوا للسماء إليك

ولم يبق لي من بقاء هنا غيرُ أشلائهم

ونهارٍ يئنُّ وريشِ حمَامٍ على العتباتِ وأسمائهم.

أصابعُهم شمس هذا الفراش وجرحُ المدى

لم أقُلْ للفَراش هنا أي شيء

تركتُ الفراش كروحي يرفرف بين أصابعهم ويسافرُ بين الرّمادِ وبين النّدى

سأغنّي لهم باسم عشرينَ ألفًا. . . ثلاثين . . .

قاموا على أرضنا

لن أقول: السّلام لمن يَقتُلون ومن يَقلعُون ومن يَحرقونَ

السّلامُ على الأرض كان لنا قبْلَهم ههنا. . .

والسلام على الأرض يبقى لنا بعدَهم ههنا. . .

السّلام لنا

السلام لنا

* الجملة للشاعر الشهيد رفعت العرعير

Ibrahim Nasrallah was born in 1954 to Palestinian parents who were uprooted from their land in 1948. He spent his childhood and youth in the Alwehdat Palestinian refugee camp in Amman, Jordan, and began his working life as a teacher in Saudi Arabia. He has been a full-time writer since 2006, publishing fourteen poetry collections and twenty-two novels. Four of his novels and a volume of poetry have been translated into English, including his novel Time of White Horses, which was shortlisted for the International Prize for Arabic Fiction in 2009. He is also an artist and photographer and has had four solo exhibitions of his photography. He has won eight literary prizes, among them the prestigious Sultan Owais Literary Award for Poetry in 1997. In 2020, he became the first Arabic writer to be awarded the Katara Prize for Arabic Novels for the second time for his novel A Tank Under the Christmas Tree.

Huda Fakhreddine is associate professor of Arabic literature at the University of Pennsylvania. She is a writer, a translator, and the author of several scholarly books.

Toward a Free Palestine: Resources to Learn About and Act for Palestine

We are proud to present this text as part of a list of resources to take action for and learn about Palestine, as well as works by Palestinian artists, writers, activists, and cultural workers.