January 8, 2024

The Writing of Pain

by Maya Abu Al-Hayyat, trans. by Nour Eldin Hussein

The following is a section from the forthcoming book On Time and Pain, written and edited by Maya Abu Al-Hayyat, published by the Palestinian Writing Workshop as part of the larger project Burning Time: Interviews, Texts, Visions, and Thoughts in partnership with the Rights for Time network.

As the genocide in Gaza enters its fourth month, Mizna is honored to feature the work of Palestinian novelist and poet Maya Abu Al-Hayyat. The Writing of Pain concerns itself with forging a path through the distortion of time and space created by imprisonment and of tragedy suffered through occupation. Abu Al-Hayyat’s prose confronts the bloat of memory, the difficulty of contemplating that for which there is no record, and seeks “a way to describe the truth without plunging into the wound.” Winding through a series of files and asides, Maya Abu Al-Hayyat demonstrates how the only remedy against the mutiny of memory is not a tighter grip, but greater care.

—Nour Eldin H., Mizna editor and translator

My friend says, why do you rob the characters of their right to speak, why don’t you narrate Esmat’s real story, why don’t we know Layan Kayed’s story except through what you tell us, why doesn’t Nadir el-Saamry speak? I reply that these stories are not journalism—why does everything have to be so clear and detailed if a story is all we know about a person?

— Maya Abu Al-Hayyat

The writer searches for a way to describe the truth without plunging into the wound. This is a mechanical act, one that strips people of their humanity and relishes in writing the bitterness hidden on the blank page. She found, over the course of her previous experiences with pain and writing, that this is the best way to document painful stories. This way detaches the researcher and the writer from the story’s events, manufacturing credibility for the text and the voice that springs from it; this way prompts the reader to finish reading while feeling like no ideological motivations impel the writing.

The truth is that, when the agony is real, there is no enduring it. But wrapping it in coldness, shedding the sentimentality, hurling it away—this makes the pain possible to touch without opening up too many lesions. She had arrived at many truths throughout her long journey writing on the pains of others, the most important of which being that there is no need to compel people to feel the suffering of another—at least on this patch of earth, that moment of collapse comes for all. Thus the true test of your resistance lies in removing that moment as far away as possible, in becoming capable of passing by overhead while sustaining the fewest possible losses. Do not live the pain of others any more than necessary, for doing so amounts to nothing but more victims and the truth is that we are in need of survivors: victims only fuel the coffers of the humanitarian organizations, nothing more.

The writer opens up her Macbook, colored cool silver, and notes the things people say. She appears utterly serious and concentrated, trying not to comment on the dramatic stories and events that surround her except to clarify their trajectory or to confirm a detail perhaps put forward by mistake. Then, when the tears well up in her eyes—her eyes operating at a remove from the rest of her body—she resorts to apologizing: something to allow her a chance to explain her strange behavior in this world submerged in a drama senseless to any difference between the writer or the doctor or the baker or the sanitation worker or the mother. She says her sentence hurriedly, “I am sorry if I seem insensitive—this is how I cope.” She gathers up the elements of the story—specifies the setting and the time and the moment that split life in two—as she goes to wipe her tears with overt gravity. She lays open a new file on the desk surface, as it is impossible to gather all that pain in just one.

File 1: Layan Kayed

Layan Kayed was arrested again while I was in the process of gathering these stories—she had repeated a sentence I’d heard often from female detainees: “Imprisonment the first time is different: there’s mystery and discovery and fear and conflicting emotions. But the second time is abhorrent: there’s a sense of tedious reiteration, of scenes I’ve tried long and hard to wipe from my life. It’s repugnant, filled only with the stench of prison.”

I had sent a message to Layan just a single day before her jailing:

“Salam Layan. I’m writing a literary text about the people who’ve gone through difficult experiences in Palestine and I’d like to ask you specifically if you’re able to answer: what is your understanding of time before and after imprisonment? I mean, how do you see and interact with time before imprisonment and during imprisonment and after imprisonment? How do you understand the minute and the day and the year?”

Even now, Layan has not replied to the message. So I will not write Layan’s story here, as it is impossible to write the story of someone who does not want it written.

I first met her at a workshop held by the Addameer Prisoner Support and Human Rights Association that works with a group of prisoners in a number of physical and psychological rehabilitation programs after their exposure to imprisonment. The group included female ex-detainees of different ages from different towns—Layan was the youngest of them. Her writings were full of an endless panting; you hear it in her voice, in how it swallows the last letter of a word. I met up with her once on the street. She was agitated, having entered elections for student government at Birzeit University. She told me of the student body’s bad faith about the gap between the idealism she believes in and the truth on the ground. She was angry, extremely troubled. I have watched that anger on the faces of many pure-hearted Palestinians over the course of my life: most of the time, that disappointment drives you to withdraw from politics, from collective action, from speaking about what you’re thinking aloud so as to protect your principles and your ideals. Over time, it drives you to busy yourself with your own personal minutiae. In this way, spaces are emptied of the pure-hearted, and filled with hypocrites.

They imprisoned Layan a second time, and in all likelihood will imprison her a third time and a fourth. I saw her after that second stint, which lasted over two months; she was with a group of friends—she seemed loved, not defeated. She emphasized the cruelty and the ugliness of that second imprisonment. It’s difficult to say anything to someone just released from prison: you don’t know whether to congratulate them, or to console them. They’ve stolen their time, a chunk of their life; the jailer punctured holes in their psyche and in their relations with others, have wounded provinces in their memory, and the traumas to be revealed in time will surface in the shape of their relationships and in their fear and in their gait and in their gestures. There are no reparations for that.

I thought I would write this to chronicle a moment in Layan’s life, to explore what will happen to her twenty years from now.

An Aside

A newscaster asks me what will happen to art in fifty years; a book editor asks me what will happen one hundred years after the Nakba.

But despite the fact that I am a writer, imagining the future—even conjuring it up fictionally—is an act I cannot do, ever. Some attribute this to creative inadequacy, while others analyze this in terms of the psychological traumas sustained by those downtrodden individuals whose imaginations cease exploring the bright side—the future being that darkened territory.

Now is the future in the story of Nadir el-Saamry—my friend from university who spent twenty-two years in prison. I graduated and married and birthed children while he was in prison. I do not know what he has done there—does he measure time with the things he does? Is he living his own future, or does he relive one past stretched out?

Does time stop in prison because the things that happen there are limited—confined to eating and drinking and sleeping and counting and bathing—or is it our method of progression that is twisted? The march of time must follow this scene of modernity we manufactured, tied to capitalist ideals of work and achievement. And yet it is freedom that is the missing element here, the idea that you own (or think that you own) the freedom to do as you please. It is the concept of (imagined) freedom that is unmasked in the prison, its meanings bare and clear—you don’t possess freedom, but what if you manage to twist the truth yet again, and write, as Esmat Mansour does in Prison of the Prison, such that it is you who is free, and everything else imprisoned.

File 2: Woman in the Salon

“When I saw him in the courthouse I slapped him, I told him how have I managed to let three months fly by without seeing you, even for a day? He got locked up before, and when he got out he didn’t sit at home even for a moment—he just wanted to get out, live, see his friends.”

“A soldier pretending to take pity on him tells me shame on you, why did you hit him like that? and I told him stay out of it, I said, when we yearn, we hit each other.“

“The first time they locked him up it wasn’t like that. The second time, something in his voice broke. He keeps telling me, I don’t understand why they took me., I don’t have to be here. He’s going to lose his mind. For a year and three months they kept extending his administrative detention.”

She took out her phone and looked through the pictures, holding it out toward me and gesturing to it.

“He looks good, right? When he got out the second time his body filled out, got big suddenly—I go absolutely crazy for him, God protect him.”

“When I hear about his martyred friends I thank God he’s in prison and not out here.”

And then she informs the salon owner to trim the back of her hair, stressing sternly not to cut it too short. I was going to ask her, could I get your permission to record your story? But I opted instead to carry on playing the role of the client, annoyed at the tardiness of the salon owner.

Should I publish this story? Without the names, it’ll be just a story I heard on the street—perhaps I’ll publish all the stories I hear on the street. The story of the guava vendor, for example? I repeated his story a hundred times during a poetry tour: I wanted a theory of poetry, so I said it is that unknown quantity between the guava vendor and the customer going to America the next day, and he tells her about his mother who’s staying at Hadassah Hospital because of her cancer and how they had barred him from visiting her because he used to be a prisoner; his body was big and muscular, and one could see tears in the corner of his left eye, and she wanted to embrace him but to imagine that—to add a guava vendor to one’s account—was terrifying. He told her his story because she lived in Jerusalem and could reach his mother, despite the fact that she never will. Perhaps I’ll write about his longing to cry, or the writer’s longing, never to be realized, to stroke his hand, as she ponders that this is what poetry is. It was no more than that—just a conversation between a guava vendor and a writer—but it resulted in long discussions about the essence of poetry: it is what is left unsaid between the guava vendor and the writer desiring to arrive at the other end of the world.

File 3: Esmat Mansour

Esmat Mansour was imprisoned when he was seventeen years old, and spent twenty years jailed. I got to know Esmat when he called me from prison—I was on my way to drop my kids off at their preschool, performing the million tasks asked of a working mother of twins whose husband does not even help with the frying of eggs.

He spoke through a smuggled flip phone—an incredible achievement in the prison—and yet he was calm. He could call me for hours without any regard for the time, while I’m on the other end trying to catch up with time before it runs out. He wanted to write a novel with me by exchanging letters, but I did not have the time nor the energy nor the desire nor the need, in all likelihood. I introduced him to a writer friend who did have the sufficient time to spend on an imprisoned man, and indeed they spent hours and days and wrote a joint novel that never saw the light of day, likely because it fell into the trap of sentimentality.

Esmat got out of prison after twenty years. Despite being thirty-seven—tall and handsome, his hair gray—he left as a child. There were stories repeated about his dramatic romantic relationships in prison; he married immediately upon his exit (to a relative, it is thought), became a father of two, and he now works in Hebrew translation and literature.

He wrote a number of novels in and out of the prison, the most important of which being Prison of the Prison. Likely what makes him distinct is that he’s still able to laugh at himself without aggrandizing or feeling shame.

I ask Esmat, what is time before and time now?

“Time in the prison runs parallel to actual time.”

A time where nothing happens, the same faces and places and appearances, no variation, hard and unyielding; changes measured only by family visitations every fifteen days, by one hunger strike to the next, by one anniversary of imprisonment to the next.

Before prison, time was tied to school or graduating from school. In the countryside there are the seasons: the season of olives, the season of apricots, the season of harvest and the homecoming of those away. Events associated with the human being’s relationship with nature, with growth and proliferation.

Now, you race time.

You are slow, and it sprints away from you.

Time is not enough, it passes quickly. There are hundreds of things you must now chase after and achieve, as if time flees: your family, your children growing up, payday.

It is only outside of the prison that there exists the hour and the day. In prison there is no interest in the small units—that is time you rather wish to pass quickly. Things that happen shrink the units of time, they make them smaller.

Esmat goes quiet, and he continues living his life, and this is an incredible thing, and sometimes it might seem that this is all you can hope for.

An Aside

My friend says, why do you rob the characters of their right to speak, why don’t you narrate Esmat’s real story, why don’t we know Layan Kayed’s story except through what you tell us, why doesn’t Nadir el-Saamry speak? I reply that these stories are not journalism—why does everything have to be so clear and detailed if a story is all we know about a person? Later, however, I would in fact try to paint a picture of a person for them; this is difficult, because they are real.

Look up Nadir el-Saamry (نادر السامري) right now. Go onto Google and look for his pictures. You’ll find one where he’s sitting cross-legged, wearing a smile that almost jumps from the screen and into our embrace. It is as if he just got his hair cut. In another picture, it seems he’s at university, wrapped in a red kufiyyeh I’ve seen tens of times, and wearing an ‘80s style jacket. He’s speaking into a microphone like a political orator. His voice jumps into my ear; his beautiful voice that seems as if he’s eating something while speaking, thick hair, waist thinner than it should be, a Samaritan, he thinks constantly of revolution (does he still?). He loved my friend, who used to sleep next to the radio when he was wanted during the Second Intifada: she was waiting to hear his name listed among the martyred. We were all relieved when we heard news of his arrest.

Is it acceptable for me to write this in a hurry as if it is unimportant? My friend stayed up waiting to hear his name on the radio, she did not sleep nor eat nor bathe—the pain did not cease. She lives now somewhere else. We do not dare ask how it is that life went on when—for that place, for that person, for their life—it stopped.

An Aside

Love produces the story of life—that is certain. But it also ends it.

Today I search for Jihad’s mother’s phone number for the twenty-third time. I will never save it in my phone, it seems, as I have memorized it by heart, and yet nonetheless I look for it anyway. That number was itself Jihad’s, and I say to myself that I will never forget it and so there’s no need to record it. It is October 1, the anniversary of his martyrdom. I almost said to her, happy holidays. We call each other every year on this date, but we do not mention why it is we do so—it is an anniversary we do not yet dare speak of aloud. For the twenty-third time in a row, Jihad is martyred, this recurrent death that will likely only cease when we all do—all who knew him, all who chanced upon him.

It recurs every time I see an old friend I hardly remember, ”I knew you in the days of Jihad!” And it seems that the days of Jihad were an era unto itself, with a different sky and another earth and sweets and falafel and streets and books and readings and other people. Everything other—another God and other relationships, other desires and sighs and songs.

And everytime I enter a relationship, I return to that relentless devastation—the devastation of loss, of rupture, the devastation of grief, of leaving behind.

I decided to love five at once. I made this decision recently—it is the only way I can sate the massive, unexplainable void. I devour love and relationships and care—who can shoulder the burden of all that loss, without feeling listless and disgusted? Of my ceaseless needs: to chase away that crippling fear of being alone again, of experiencing that inscrutable feeling of calling out for someone who will never hear, despite screaming in the void.

Look up Jihad el-Aloul (جهاد العالول) on Google, you will find him there, with his beige pants and puffy black jacket. I do not like the pictures on Google. I spent a long while trying to remember what he looked like, but my memory played with me a game of erasure, extremely rapid—I chase after the smallest glimpse before it is wiped out, only for it to evaporate before I can grab hold of it.

Maya Abu Al-Hayyat (1980) is a Palestinian novelist, poet, and translator, born in Beirut and living in Jerusalem. Since her first publication in 2004, Habat Min Alsukar (Sugar Pearls), she has published numerous novels and children’s books as well as four collections of poetry. A volume of poems selected and translated by Fady Joudah, You Can Be the Last Leaf, was published by Milkweed Editions (Minneapolis) in 2022 in English translation. Her poems, translated into English, French, German, Korean, and Swedish, have appeared in Los Angeles Review of Books, Cordite Poetry Review, the Guardian, and Literary Hub. Since 2013, Maya Abu Al-Hayyat has directed the Palestine Writing Workshop, an institution that encourages reading through creative writing and storytelling projects with children and teachers

Nour Eldin H. is an Egyptian essayist, editor, researcher, translator, and enthusiast of the written and spoken word. He is currently on staff at Mizna completing a fellowship with the National Network for Arab American Communities (NNAAC). He lives, works, and studies in Minneapolis, where he is pursuing an M.A. in Arab culture studies focusing on Egyptian rap. He maintains a small blog on Substack (lightedroom) where he writes about Arab digital culture and life online.

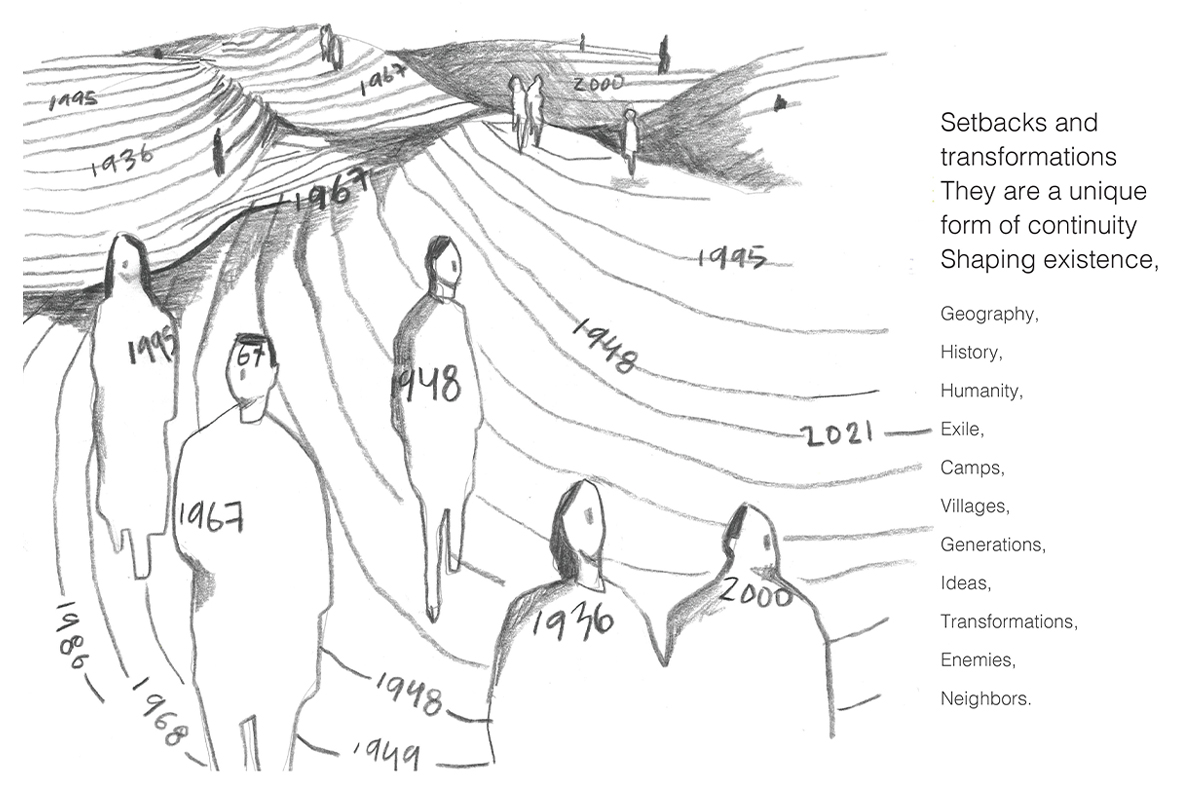

Header image: The Moments That Changed the Shape of My Life ©PWW Artwork: Yara Bamieh Text: Maya Abu Al-Hayyat

Toward a Free Palestine: Resources to Learn About and Act for Palestine

We are proud to present this text as part of a list of resources to take action for and learn about Palestine, as well as works by Palestinian artists, writers, activists, and cultural workers.